2. Book Two: Theory#

2.1. Watering Down the Dharma#

I have been accused of “watering down the dharma.” By defining an arahat (also arhat and arahant) as someone who has “gotten off the ride” and can see experience as process, as opposed to a cartoon saint, I have ruffled more than a few feathers. Here are some questions, along with my responses:

Why are you redefining the Four Paths of Theravada Buddhism?

There is an old joke in which a man is asked, “Do you still beat your wife?” The person being asked is put into an untenable situation by the false assumption built into the question. The assumption is that you have beaten your wife in the past. If you answer “no,” the questioner will follow up with “when did you stop?”

Best to reject the question entirely.

Why are you redefining the Four Paths?

I reject the question. It is false to assume that there is One Right Way to interpret ancient texts, providing an infallible orthodoxy against which all other interpretations must be compared and inevitably found lacking. There is no One Right Way.

The authors who penned the early Buddhist texts are no longer available for comment. We can only guess at their intentions. Modern commentators who insist that they know the original meaning of arahat are overplaying their hand, regardless of how scholarly or ostensibly traditional their arguments.

Like everyone else who has an opinion about this, I am simply throwing my hat into the ring; I offer one possible interpretation of the Four Paths model. This interpretation is based on the Pali Canon and commentaries, rooted in observed reality, and nurtured by pragmatism. Implausible claims are sooner discarded than taken at face value. But even after discarding the implausible, the unprovable, and the downright silly, what is left is too good to ignore; enlightenment is much more than a myth, it happens to real people in our own time, and it can be systematically developed through known practices.

It seems likely that the Buddhist definition of “fully enlightened” changed over time in a kind of slow motion frenzy of one-upmanship. Here is a passage from palikanon.com, attributed to W.G. Weeraratne, author of several books on Buddhism and editor-in-chief of the prodigiously researched Encyclopaedia of Buddhism, published by the government of Sri Lanka:

In its usage in early Buddhism the term [arahant] denotes a person who had gained insight into the true nature of things (yathābhūtañana). In the Buddhist movement the Buddha was the first arahant… The Buddha is said to be equal to an arahant in point of attainment, the only distinction being that the Buddha was the pioneer on the path to that attainment, while arahants are those who attain the same state having followed the path trodden by the Buddha. http://www.palikanon.com/english/pali_names/ay/arahat.htm

Note that “insight into the true nature of things” sounds as though it might be within reach of anyone. (In a moment, we’ll discuss what the early Buddhists believed this “true nature” to be.) And indeed it was not the least bit unusual for people practicing the Buddha’s system to become “fully enlightened arahats” according to early Buddhist texts. But look what happened next:

But, as time passed, the Buddha-concept developed and special attributes were assigned to the Buddha. A Buddha possesses the six fold super-knowledge (chalabhiññā); he has matured the thirty-seven limbs of enlightenment (bodhipakkhika dhamma); in him compassion (karunā) and insight (paññā) develop to their fullest; all the major and minor characteristics of a great man (mahāpurisa) appear on his body; he is possessed of the ten powers (dasa bala) and the four confidences (catu vesārajja); and he has had to practise the ten perfections (pāramitā) during a long period of time in the past.

When speaking of arahants these attributes are never mentioned together, though a particular arahant may have one, two or more of the attributes discussed in connection with the Buddha (S.II.217, 222). In the Nidāna Samyutta (S.II.120-6) a group of bhikkhus who proclaimed their attainment of arahantship, when questioned by their colleagues about it, denied that they had developed the five kinds of super-knowledge—namely, psychic power (iddhi-vidhā), divine ear (dibba-sota), knowledge of others’ minds (paracitta-vijānana), power to recall to mind past births (pubbenivāsānussati) and knowledge regarding other peoples’ rebirths (cutū-papatti)—and declared that they had attained arahantship by developing wisdom (paññā-vimutti). http://www.palikanon.com/english/pali_names/ay/arahat.htm

Hmmm… So it looks as though the meanings of the words Buddha and arahat changed over time, with more and more powers and attributes layered on. Eventually, the lists of things arahats could do and the lists of things they had left behind became so long that no living person, past or present could reasonably be expected to make the cut. This is where we find ourselves today, assuming we believe the currently popular (among Buddhists) kitchen-sink version of enlightenment.

Let’s go back to the beginning for a moment.

In its usage in early Buddhism the term [arahat] denotes a person who had gained insight into the true nature of things.

It would be useful to know what the early Buddhists may have meant by the “true nature of things.” Here is more from Weeraratne:

At the outset, once an adherent realised the true nature of things, i.e., that whatever has arisen (samudaya-dhamma) naturally has a ceasing-to-be (nirodhā-dhamma), he was called an arahant… http://www.palikanon.com/english/pali_names/ay/arahat.htm

Are you seeing what I’m seeing? Not only is full enlightenment (arahatship) a perfectly reasonable thing for ordinary people to aspire to and attain, the Buddha himself was initially considered just another enlightened man, albeit the first of his group. All that was required was to see that anything that “has arisen, naturally has a ceasing-to-be.” (And may I humbly submit that this is precisely what I mean when I advocate learning to see this experience as process. While trivial as a mere concept, the ability to see this in real time is life-changing.) I find this empowering beyond words. Although I would be perfectly willing to dispense with Buddhism entirely if it did not have anything to offer us at this point in our history, I love the fact that 2500 years ago, humans discovered a technology for mental development that still works today. And I love the fact that once you strip away the accretions of thousands of years of can-you-top-this storytellers, it all seems perfectly do-able to us ordinary folks. It is perfectly do-able, of course, and this is my entire point.

In interpreting ancient Buddhist maps, it is necessary to begin with a few assumptions. Here are mine: I begin with the assumption that the chroniclers of early Buddhism were pointing to something that was happening around them (or to them), but were limited by the obligatory biography-as-hagiography storytelling style of their day. I continue with the assumption that what was possible in the 5th Century BCE is still possible today. Next, I strip away the implausible and preserve the plausible. It is implausible that ancient meditators defied gravity, traveled through time, performed miracles, or overcame their human biology. On the other hand, it is plausible that awakening, as it was then understood, was commonplace among meditators in the time of the Buddha. (A common theme of early Buddhist documents is that nearly everyone who did the Buddha’s practice became fully enlightened.) I conclude that there is an organic process of development that results from meditation. It need not be mystical or magical, and we can just as easily think of it as brain development. Finally, and most importantly, I reality-test these assumptions with observations of present day humans, using my subjective experience, interviews with other meditators, and the carefully documented reports of present-day meditators available in books and online forums.

Before I present a side-by-side comparison of two competing models of arahatship, we might reasonably ask whether a stage model of contemplative development has any value at all. I believe it does. Humans learn best when they are given discrete goals and regular assessments of progress. I have heard the protestations of those who believe that meditation must never be a goal-oriented activity, and that this holy truth renders all stage models either counterproductive or irrelevant. I refer such people to the success of my students. And for those who crave a more authoritative (authoritarian?) voice, I would point out that according to that most definitive of Buddhist sources, the Pali Canon, the dying words of the Buddha were “Strive diligently.”

We can compare and contrast my model (let’s call it the Pragmatic Model) with a model that is currently in vogue among Buddhists, and which we might reasonably call the Saint Model. First, the definitions:

2.1.1. The Pragmatic Model of Arahatship#

These people know they are done; they have come to the end of seeking. Although they may continue to meditate with great enthusiasm, and continue to deepen and refine important aspects of their understanding throughout their lives, they do not feel there is anything they need to do vis a vis their own awakening. This is in marked contrast to the pre-arahat meditator, who tends to be obsessed with meditation and progress. Equally important, the Pragmatic Model arahat is able to see experience as process. There is no enduring sense of self at the center of experience. The Buddhist ideal of insight into not-self has been completely realized and integrated.

2.1.2. The Saint Model of Arahatship#

This person does not suffer. No negative emotion is felt or expressed. Ever. (I have emphasized the expression of negative emotions because there will always be individuals who claim not to feel negative emotions even while expressing them in a way that is obvious to everyone around them. Doesn’t count.) No anger, resentment, annoyance, irritation, aversion, impatience, or restlessness is allowed. There is no sensual desire, and this applies to both food and sex. This person cannot compare himself/herself with others, either favorably or unfavorably. This person is unable to lie, steal, speak harshly, or kill a sentient being, including insects. Did I mention omniscience and diverse psychic powers including mind reading? This person is a saint by the most rigorous interpretation of the word.

2.1.3. Comparing the models#

For a developmental model to be relevant to modern humans, it should describe something that actually happens and can be observed today. It should happen often enough to form a reasonable sample size for study. The Pragmatic Model does this. I estimate that I have communicated with 20-30 people who might be considered arahats by this model. Since I personally know only a tiny fraction of the humans on Earth, it is reasonable to assume that this is only the tip of the iceberg, and there are many hundreds or thousands of such people whom I have not yet met.

By contrast, the Saint Model is a high bar indeed. I have never met anyone who could approach it, in spite of the fact that in the natural course of my life, first as dedicated seeker, and later as meditation teacher, I have met many highly accomplished and/or revered meditators. As for dead saints, in many cases there is little record of the phenomenology of their day-to-day experience, either subjective or as observed by others. In cases where there is such a record, candidates are quickly eliminated from the Saint Model for displaying or reporting unseemly amounts of human behavior.

A useful model describes a repeatable process and has clear metrics for success. The Pragmatic Model identifies specific phenomena that are experienced by the meditator at each stage along a typical sequence of events. (See, for example, the Progress of Insight section of this book, and my criteria for attainment of each of the Four Paths.) The Saint Model, on the other hand, does not offer clear metrics for success, either in the beginning or the middle. In the end, you will know you have achieved it because you will never experience or express irritation, and you will lose your enjoyment of food.

2.1.4. The Hercules Effect: Why “watering down” a high standard might be a good idea#

In Greco-Roman mythology, Hercules was the very embodiment of physical fitness. He did a great deal of slaying and capturing in his illustrious career, and even had time to hold up the world for a moment when Atlas needed a break. Hercules was invincible and almost infinitely strong. Compared to Hercules, the most decorated athletes of our own day are scarcely worth mentioning. Hercules would outbox Mike Tyson with one hand while simultaneously defeating Serena Williams at tennis and Michael Jordan (in his prime!) at basketball. Are we watering down our definition of physical fitness by not believing in Hercules? Or are we simply acknowledging that Hercules is but a myth and is therefore not relevant to us as we probe the limits of human excellence?

Similarly, we can dispense with the myth of enlightened sainthood and concentrate on what actually happens to flesh and blood humans when they meditate. We can define enlightenment/awakening in a way that comports with observed reality. A four paths model that is teachable and learnable is infinitely more interesting than one that never happens. We stopped believing in Hercules some time ago. Perhaps it’s time to stop believing in magical cartoon saints. This is an eminently practical step, as letting go of our fantasies allows us to focus on meditation in earnest. And effective meditation practice allows us to realize the remarkable benefits of awakening for ourselves, rather than through the intermediary of an imagined champion.

2.2. Fluency with the the Ladder of Abstraction#

Neuroscience informs us that everything we experience is a representation in the brain. We have no direct pipeline to the external world. I see a wall across the room. It is beige, with white trim, and littered with purple sticky notes in book outline form. But my experience of that wall is a mental construct based on photons hitting my eyes or pressure sensations hitting my fingers. Some mystics have intuitively realized this and concluded that external reality is therefore an illusion. I find this conclusion fallacious. I have every reason to believe that 20 years from now other people will still be able to see and touch the wall across the room, and cover it with their own sticky notes. The external world is not an illusion. But my experience of it is an abstraction. What this means is that even when I go as low as possible on a ladder of abstraction, it is still an abstraction. Fine. Fair enough. For our purposes, it is sufficient to identify a continuum of abstraction from lower to higher.

Lower levels of abstraction are, by definition, more grounded in the five physical senses. Higher levels allow the naming of things, memories, projections of imaginary worlds, and manipulation of concepts. Dogs, cats, birds, lizards, and snails have access to lower levels of abstraction, but cannot go as high as we can on the ladder. They can experience input from the five senses, and create a mental representation of their environment. Some non-human animals can even abstract to the level of assigning labels to things. But they presumably cannot do math or spin multiple elaborate scenarios about the future. They cannot be architects or diagnosticians. The ability to move high on the ladder of abstraction is uniquely human (at least on this planet) and it has served us well. We are fruitful. We multiply. And there is the individual payoff; if you can out-plan your neighbor, you will prosper. But there is a cost. There is a cost! Higher levels of abstraction are inherently agitating. We are happy to pay the cost because the payoff is so great. Still… the cost. Our inability to return to low levels of abstraction makes us sick and kills us early. We are awash in a sea of stress and anxiety. We must re-learn the art of climbing back down the ladder of abstraction. We must learn to be simple sometimes. Not all the time. Sometimes. One of the benefits of meditation, one of the specialties held under the over-arching umbrella of contemplative fitness, is the art of simplicity. To go low on the ladder of abstraction. To breathe. To relax.

With this in mind, we can identify fluency as a core value and a core competency within contemplative fitness. We can train ourselves to access the ladder of abstraction in its entirety, from low to high, and back down again.

2.3. The three speed transmission#

The three speed transmission is a conceptual framework for understanding the ways in which contemplative practices from various traditions complement one another. It grew out of my need to make sense of the different, often contradictory teachings and techniques I encountered from various contemplative traditions and teachers. Think of it as a tree to hang your knowledge on. It will help you organize your thoughts. This kind of knowledge tree is called a schema. Here is the three speed transmission schema in a nutshell:

First gear: What?

Second gear: Who?

Third gear: Stop practicing; this is it.

At a slightly higher level of detail, here it is again:

First Gear: Bring attention to the experience of this moment. Objectify (take as object) the simple phenomena of the six sense doors, which are seeing, hearing, tasting, touching, smelling, and thinking. Pure concentration practices also fall under the First Gear heading.

Second Gear: Bring attention to the apparent knower of this experience. Typical guiding questions are “Who am I?” or “To whom is this happening?”

Third Gear: This is it. It’s over. Surrender to the situation as it is in this moment. Then, go beyond even surrender, to the simple acknowledgement that this moment is as it is, with or without your approval. Even your effort to surrender is a presumption, a last-ditch effort to control the situation; by agreeing to surrender, you imply that you have a choice, as though you could choose not to surrender. This is not so. You are not in charge. You are the kid in the the back seat with the plastic steering wheel. This moment is already here and nothing you can do or not do in this moment will change it.

Here is a third iteration of the schema with a partial list of practices that correspond to each gear:

First gear:

Vipassana meditation, with or without following the breath, noting aloud or silently, Burmese Mahasi-style, interactively or alone; body scanning vipassana, as taught in the U Ba Kin/Goenka tradition of Burma.

Pure concentration practices like mantra (repeating a word); gazing at an object; counting the breath; repeating metta (lovingkingdness) or compassion phrases; focusing on feelings of metta or compassion; concentrating on a conceptual object, i.e., visualization of deities, lights, or physical objects.

Ecstatic dancing, whirling, or speaking in tongues.

Second gear:

Self-enquiry as taught in Advaita Vedanta; hua tou as taught in Chinese Zen (Chan) and Korean Zen (Seon).

Third Gear:

Shikantaza (just sitting), as taught in Japanese Soto Zen; turning toward the “un-manifest” as in Mahamudra or Dzogchen practices; “Just stop!” as taught by Advaita teacher Poonja-ji. Being reminded by a teacher that you are “already enlightened” or that you “cannot do it wrong,” as taught by some neo-advaita teachers, e.g., Ganga-ji, Mooji.

When I first became interested in contemplative practice, I read a number of Zen books that made reference to “awakening” or “enlightenment.” It seemed to be some nebulous sort of wisdom that Zen masters had. The reader was often encouraged to abandon the quest for enlightenment, even though enlightenment was clearly the goal. If one could just adopt the right attitude, enlightenment would arise; but if you tried to “get” it, you would fail. Paradox was everywhere. The aspirant must understand that there is “nowhere to go, nothing to get.” That sort of thing. It was never clear to me how I could duplicate this highly touted but under-explained wisdom in my own life. As a westerner who did not have access to traditional Japanese culture, and who grew up with the understanding that learning resulted from a fairly straightforward process of education, I found the Zen approach less than helpful.

Since I never felt called to put on a black robe and join a Zen center, I was on my own. I didn’t know how to develop my meditation practice other than to read books about it and sit for thirty minutes a day counting my breath from one to ten (a practice I had learned from a Zen book). I sensed progress in my meditation practice throughout this time, but I had the distinct feeling that I was missing something and that my practice was inefficient.

When I met Bill Hamilton in 1990, he told me about the Theravada Buddhist four paths of enlightenment and the Progress of Insight map. During this time, I also learned that according to the Pali suttas, the dying words of the Buddha were “appamadhena sampadetha,” which means “strive diligently.”

This linear, goal-oriented approach made sense to me, given my own cultural influences, and I was immediately able to put this simple concept to work; the more I practiced, the more I progressed. Thirty minutes a day was not enough; I practiced more, understanding that progress was proportional to time spent training. And technique mattered; Mahasi-style mental noting, with its built-in feedback loop and systematic way of including all aspects of experience, was sure to be more efficient than simple breath-counting. “Aha!” I thought. “There is somewhere to go and something to get.” It was clear that the Pali Buddha [Although both the Pali and Sanskrit texts are ostensibly about the same historical figure, the pictures painted by these collections of stories diverge; the Buddha of the Pali Canon is fierce, clear in his communication, and uncompromising in his dedication to excellence while the Buddha of the Sanskrit texts often appears easy-going and vague. This is what I mean when I say “Pali Buddha” or “Sanskrit Buddha.] wasn’t into this nebulous “you can’t get there from here” baloney at all. My practice took off like a rocket. Here was a straightforward, systematic pedagogy, and it worked. Vipassana seemed to make Zen irrelevant. But that wasn’t the end of the story.

In the early nineties, while living and meditating intensively in a Burmese-style Mahasi monastery in Malaysia, I met an American Zen practitioner who said that the Burmese vipassana approach was wrong-headed and that the Zen people had it right after all. He insisted that the striving that was part and parcel of the Burmese vipassana scene was just the initial practice and that eventually you had to grow up, stop banging your head against the wall and let things be as they are. I spent many hours arguing with this fellow, but it was clear to me that he had a valid point of view that wasn’t being expressed by my Burmese teachers. I chewed on this for several years, flip-flopping between thinking that the Burmese were right and the Japanese clueless, and then deciding that the Japanese were right after all, and so on.

In the early and mid 2000s, I became fascinated with Advaita Vedanta and the process of self-enquiry as taught by Ramana Maharshi and Nisargadatta. Here was yet another lens: you didn’t have to pay attention to anything other than the apparent self, and by asking the question “who am I?” you could deconstruct this sticky illusion and lose the sense of self forever, essentially solving all of your problems. Self-enquiry had the benefit of simplicity; rather than the myriad changing objects of vipassana, there was only one. It was arguably harder to get lost while meditating, since the task was to keep the attention firmly on the question “who am I?” From the point of view of Advaita, neither Zen breath-counting, nor Zen surrender, nor Burmese vipassana have much to offer;[In all fairness to the vast and multi-faceted Zen tradition, self-enquiry is emphasized in Korean Zen (Seon or Son), and some schools of Chinese Zen (Chan).] it’s all about directly investigating the apparent self. All questions are immediately redirected to self-enquiry. Who cares what is happening? Only ask to whom it is happening. The recursion of this approach creates a practice that is both elegantly simple and completely self-contained. I liked it, and I jumped into the practice with both feet; my pendulum swung again and I became dismissive of both Zen and vipassana. Ramana Maharshi became my hero and I spat on anyone who wasn’t hip enough to practice self-enquiry to the exclusion of all else.

For many years, I was unable to see how these perspectives could be reconciled; I gravitated toward whatever felt right at the time and declared it the best and only practice. Again and again I was blinkered by the narrowness of my own perspective. Gradually, though, my viewpoint began to broaden. I could no longer deny that all of these seemingly contradictory systems had value, and more specifically that I had benefited from all of them.

I needed a conceptual framework big and flexible enough to hold the striving of the Pali Buddha, the self-enquiry of Advaita, and the surrender of Zen. I put them in that order, i.e., 1) “What?” as in “what is happening?” 2) “Who?” as in “to whom is it happening” and 3) “Stop practicing because this is it.” The three speed transmission was born. And by about 2005, I was able to see a way to integrate all three understandings into a method, using one to scaffold the next. The three speed transmission allows us to step back and see the bigger picture, allowing for the possibility that any given perspective can have great value within its sphere and that there is no one lens to rule them all.

In the end, there is no hierarchy. “Stop practicing because this is it” is not a higher-level understanding than the simple reality of the six sense doors (seeing, hearing, tasting, touching, smelling, and thinking), as viewed through vipassana noting practice. Nor is self-enquiry to be privileged over either of the other lenses. In fact, the ability to switch fluently among lenses is a hallmark of mature practice and mature understanding. There is no one lens to rule them all. As Croatian Buddhist teacher Hokai Sobol says, “every perspective both reveals and obscures.” Each lens is valid within its sphere, and effective practice becomes a simple and practical matter of applying the appropriate lens in any given moment.

The three speed transmission approach encourages you to adopt whatever lens is most helpful in a particular situation. If you observe the comings and goings of your own experience, you can see thoughts and body sensations arising and passing away. All of these phenomena can be perceived out there; I can see the computer in front of me, the man sitting at the next table in the coffee shop; I can hear the conversations going on around me, the background music playing through the sound system; I can taste my coffee; I can recognize my own thoughts and internal dialogue as I think of these examples. The practice of looking at the objects of the six senses [Buddhist theory identifies six senses: seeing, hearing, tasting, touching, smelling, and thinking. In this system, thinking is the sixth sense. It is valuable to see experience this way as it counters the tendency to privilege thinking as somehow more “me” then other phenomena. Ultimately, all phenomena, including the momentarily arising sense of “I” share equal status; none is to be privileged over any other.] is vipassana. We can place this in the first gear category.

In addition to all of the objects arising within experience, there is often the sense that all of this is happening to me. All of this stuff happening out there is being perceived by me in here. I’m looking out at something, so I must be the one who is looking. In second gear, we investigate this sense of subject, this sense of I to whom all of this happening. Any practice that directly targets the apparent sense of self falls into the category of second gear.

It could be argued that third gear, in its purest form, is not really a practice at all; it is complete acknowledgement of and surrender to the situation as it is. Such is the intention behind the “just sitting” practice of Soto Zen as well as certain practices within the Tibetan Buddhist traditions of Dzogchen and Mahamudra.

Understanding that the best practice is the one that is most beneficial in this moment, we can leave behind a big bucket of unnecessary suffering. When a practitioner laments the fact that she is not able to sustain herself in third gear all the time, for example, a quick detour to second gear would call into question this “self” who needs to have a particular experience. And downshifting to first gear allows for the invaluable feedback loop of noting (labeling) in order to stay on track with minimal space-outs while also reducing experience to its bare components, devoid of unnecessary rumination and worry.

The gearshift analogy points up the fact that it is possible to get more traction with noting (1st gear) than with self-enquiry (2nd gear) or surrender (3rd gear). Third gear practice is best done when there is already a good deal of momentum. The automobile transmission idea initially came from something I heard Shinzen Young say many years ago: when things were tough, he would downshift to mindfulness of the body (vipassana) as a kind of “first gear.” Once he got up a head of steam, he might shift gears to another practice, perhaps Zen shikantaza (just sitting). I found Shinzen’s downshifting idea extremely helpful and later developed it into a three-gear model, briefing flirting with a 5-speed transmission along the way.

The three speed transmission schema ties in with the idea of the yogi toolbox. There are many powerful practices for training the mind. Ideally, we collect a toolbox full of effective techniques over a lifetime. And the most important tool in the box is a kind of meta-tool that allows you to select the practice most appropriate to any given moment. This, of course, is in direct opposition to the idea that you should choose one technique and practice it for a lifetime. I don’t know anything about that, because I’ve always been eclectic and experimental in my own practice. This dynamic approach has worked for me, and this is how I teach.

Like all taxonomies, the three speed transmission is descriptive rather than prescriptive; it is not intended to tell reality how to be, but rather to give human beings a conceptual framework for understanding the reality of meditation practice as it presents itself. As such, the model is not perfect. You will be able to identify contemplative practices that do not fit neatly into any of the three categories. In such a case, the model has done its job; an exception to the model is made possible by the conceptual framework provided by the model, thus continuing to build out a scaffold upon which to hang further learning.

2.4. The progress of insight map#

[Editor’s note: Introduce and define the Progress of Insight Map before describing it in detail.] The following is a description of how the Progress of Insight stages might be experienced by an idealized meditator.

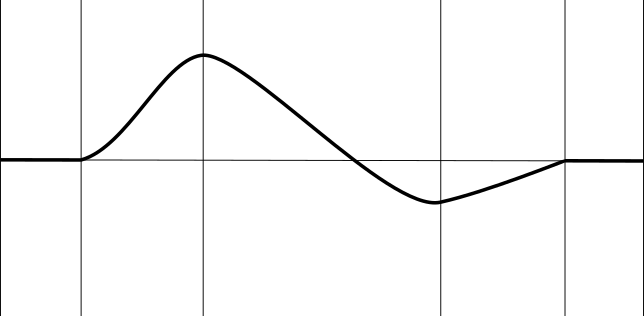

If the Progress of Insight were plotted on a graph, it would start out flat, rise until reaching a peak event, descend into a trough, stabilize, and then resolve.

The opening act is the flat line at the left, understanding that the cycle moves from left to right. (As it is a cycle, this whole process might be more accurately represented as a circle, but I have deliberately chosen a linear graph for ease of understanding.) In traditional language, what I am calling the opening act includes the first two insight knowledges: Knowledge of Mind and Body and Knowledge of Cause and Effect. [http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/mahasi/progress.html]

The ascent. The third insight knowledge, Knowledge of the Three Characteristics.

The peak. The fourth and fifth insight knowledges, Knowledge of the Arising and Passing Away of Phenomena and Knowledge of Dissolution, respectively.

The descent. The 6th through 10th insight knowledges: Fear, Misery, Disgust, Desire for Deliverance, and Re-observation. These are collectively referred to as the dukkha ñanas or the dark night of the soul.

Consolidation and Resolution. Includes the 11th insight knowledge, Knowledge of Equanimity, the 12th through 16th insight knowledges, including Path and Fruition, all five of which are said to happen in one moment, and the 17th insight knowledge, Review.

Even though not everyone will recognize all of the stages or experience them as described, the general arc holds true in most cases. It’s usually easier to recognize the stages on hindsight.

2.4.1. Knowledge of Mind and Body (Stage 1)#

The opening stage feels solid. When our imaginary idealized meditator first begins to sit down to meditate, her experience will probably be fairly pleasant and unremarkable. Soon after starting, she will have her first insight: seeing that the mind and the body are two separate things, with each influencing the other. She sees a thought arise as separate from “herself,” the knower of the thoughts. She may a notice a sensation such as an itch and recognize that it is perceived in two parts: the physical sensation itself, and the mental impression of it.

This is the beginning of a meta-awareness, a stepping back from experience to be able to dispassionately observe experience, an ability that will strengthen throughout the meditator’s life.

Our imaginary yogi has reached the first insight knowledge, the aptly named Knowledge of Mind and Body. She is just beginning to settle into meditation, which can be pleasant. There’s often a deep sense of calm and subtle exhilaration upon beginning a meditation practice. Our meditator’s experience at this point can be described as solid, because she doesn’t yet have the perceptual resolution and acuity to see things changing at a fine level of detail. The ability to perceive at the level of micro-sensations is the very heart of the vipassana technique and that which gives it its unique transformative power.

A traditional example can help to illustrate what is meant by solid in this context, and how objects that initially appear solid can be broken down into their component parts through careful observation:

Imagine that you are walking down a country road and you see what appears to be rope lying across the road, its ends disappearing into the brush on either side. As you draw closer, you notice that the rope is not lying still, as one would expect from a rope. It seems to be moving ever so slightly. Moving closer still, you realize that it is not a rope at all, but a line of ants crossing the road in both directions. Finally, you see that that line is composed of individual ants, each of which is composed of many constituent parts constantly in motion. The object of perception, which at first seemed to be a solid rope, is revealed to be a process rather than a thing.

This practice of deconstructing apparently solid objects of perception into their constituent parts is fundamental to the practice of vipassana [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vipassan%C4%81], which is translated into English as “seeing clearly.”

The meditator at the level of the first insight knowledge, however, has not yet done this. True vipassana doesn’t begin until the fourth insight knowledge, Knowledge of the Arising and Passing Away of Phenomena. It is for this reason that the A & P, as I call it, is the most important of the insight knowledges leading up to stream entry. Our imaginary yogi is not there yet, however; next in the typical sequence of events is the second insight knowledge, Knowledge of Cause and Effect.

2.4.2. Knowledge of Cause and Effect (Stage 2)#

The second insight knowledge is the direct, visceral understanding of what Buddhists call karma, as experienced in the meditator’s own life. She will feel in her gut the pain of her past unskillful actions and the joy of past good deeds. She may notice how recalling painful experiences or even imaginary arguments can lead to unpleasant sensations in the body. Likewise with pleasant memories: when she remembers the time she sent flowers to her mother for no reason, she will feel a deep happiness in mind and body. Our meditator is likely to be slightly less concentrated here than she was in the first stage, more prone to mind wandering and reflection, less able to stay focused on the objects of meditation, whether the sensations of breathing or the choiceless noting/noticing of various phenomena as they spontaneously arise. Like the first insight knowledge, this second stage is not necessarily a big deal in the meditator’s life and may go unnoticed.

2.4.3. Knowledge of the Three Characteristics (Stage 3)#

The name of this insight knowledge often leads to confusion. According to early Buddhism, the three universal characteristics of existence, also known as the three marks, are unsatisfactoriness (dukkha), impermanence (anicca), and not-self (anatta). Therefore, given the name of this, the third of the insight knowledges according to the progress of insight map, we might expect to gain deep understanding of all three characteristics at this stage. In practice, though, this stage is just unpleasant. The body feels tight, tense, and anxious. This is the stage of back pain, numb legs, distraction, discomfort, fidgeting, and boredom.

Our meditator may become obsessed with her posture at this point, looking for just the right way to sit in order to ease her discomfort.

A common landmark of the third insight knowledge is the experience of bright, persistent itching. Many mediators report solid, unbearable itches that seem to last for minutes and become more unpleasant with attention. I call the sharp, pinpoint itch the “kiss of concentration.” If you stay with one clear itch and become interested in it, it will carry you into concentration and eventually into the fourth insight knowledge, Knowledge of the Arising and Passing Away of Phenomena. If such an itch arises, become interested in it. If you are doing freestyle noting, it’s okay to just note “itching” over and over again as you focus on this one clear object. If you are using an anchor (primary object) such as the breath, drop the breath entirely and place your attention on the itch. Become the world’s greatest authority on that itch. What does it do? Does it get stronger, clearer, brighter? Does it fade, pulse or strobe? After it fades out, stay in that area of a few moments and see if it returns. Go back to random noting or your anchor only after you are certain that you have wrung every bit of useful information out of the itch (or the pulse or the throb or pain or whatever is the predominant object).

Eventually everything will open up into champagne bubble-like sensations, unitive experiences, rising energy waves, and a general sense of well-being, signaling the arrival of the fourth stage, the A&P. But you cannot skip over the unpleasantness of the third stage in order to get to the fourth. Stay with the sensations as they are, whether pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral, and let nature take its course.

The sticky places along the progress of insight are the third insight knowledge and the tenth, respectively, the ascent to the crest of the wave (3rd stage), and the descent into the trough that follows the crest (10 stage). The insight knowledge is significant in that if it is not overcome, the yogi will not progress to the all-important Arising and Passing Away of Phenomena (4th stage), and will therefore not gain access to the real fruit of contemplative practice. Having never penetrated an object of attention, the pre-4th ñana yogi will remain forever an outsider, looking in from behind the glass as others have transformitive experiences that the pre-4th ñana yogi can only imagine. Nonetheless, the 3rd ñana in itself does not present anything beyond ordinary human suffering. The pain is mostly physical, mostly experienced during formal meditation, and does not significantly affect the yogi’s life off the cushion. Such pre-4th ñana yogis, of which there are many, often become religious, adopting the ideas and trappings of whatever scene they are in. They may become devoted and much-valued members of their spiritual/religious community. But they have not yet understood the real value of this practice.

2.4.4. Knowledge of the Arising and Passing away of Phenomena (Stage 4)#

The fourth insight knowledge could be said to be the most significant event in a meditator’s career, and is often the most spectacular. This is the spiritual opening, often a completely life-changing event. This stage often involves unitive experiences, “God-union,” “the white light,” mystical visions, and sublime ecstasy. It signals the beginning of true spirituality, and while it is often mistaken for a culminating event and heralded as an experience of “enlightenment”, it is really the germination of the seed that will later come to fruition in stream entry and further developments over a lifetime.

The A&P is not a spectacular event for everyone, however; it can be a more subtle shift, with meditation becoming more pleasant and dynamic. Even if our meditator does not experience a full-blown peak experience, she will notice a change from the rough patch (3rd insight knowledge) that preceded this stage. She is likely to feel a deep gurgling joy bubbling up, rising through the body. The A&P is a very pleasant time in meditation, bringing with it a kind of orgasmic joy that dwarfs the pleasantness of the beginning stages.

It is common to experience brightness in the visual field during meditation in this stage, as if someone just turned on the lights, even with the eyes closed. Some people feel more energetic throughout the day and have trouble sleeping. Dreams may be more vivid or intense. A kind of manic joy may be experienced.

Bill Hamilton used to say that the A&P stage marks the first time the meditator has managed to completely “penetrate the object.” To use the metaphor from earlier, our meditator is now able to see the individual ants that make up what she previously saw as a rope.

The meditator has managed to reduce a seemingly solid thing to its component parts. A body sensation that was previously experienced as a solid pain in her knee while sitting is now experienced as waves of subtle twitching sensations. The clear, persistent itch from the third insight knowledge breaks down into pulses and vibrations. Thoughts, instead of sitting in the mind like stones, are seen to arise, live out their brief existence, and then vanish cleanly into the nothingness whence they came.

Sitting is effortless at this stage, and meditators tend to see their daily hours of formal practice spike upward. It is not unusual for someone in the throws of the A&P to sit for several hours a day. For a few days around the attainment of the fourth insight knowledge, all is right with the universe. The secular yogi feels enlightened, the religious yogi feels touched by God, and both expect to live out the rest of their lives at the crest of this infinite wave.

Waves, however, are not infinite, but temporal and cyclical in nature. Returning to our graph, we see that the fourth insight knowledge exists at the very peak of the cycle.

Because following the peak of every wave is a trough, there is trouble on the horizon. Mercifully, the first part of the descent is pleasant, though that may be viewed as a knife that cuts both ways as it does not prepare the meditator for the horror of what is to come. Next in line is the fifth insight knowledge, Knowledge of Dissolution.

2.4.5. Knowledge of Dissolution (Stage 5)#

The fifth insight knowledge, Knowledge of Dissolution, is a very chilled-out stage, especially compared to the overwhelming joy and excitement of the previous stage. If the A&P is orgasmic joy, dissolution is more akin to post-coital bliss.

Our meditator is in love with the world and everyone in it, but feels no compulsion to do anything about it. Our meditator’s experiences in meditation are noticeably more relaxed than they were in the previous stage, and she can easily sit for a long periods just grooving on the cool, diffuse, tingling sensations of the body.

The characteristic mind state of the fifth insight knowledge is bliss and the characteristic body sensations are coolness on the skin and tingles. The mental focus is diffuse; it’s possible to feel the skin all over the body, all at once. This is something that is difficult to do in any other stage, so when it happens, it’s a good indicator that you are moving through the dissolution stage. Bill Hamilton used to say of this stage that you feel like a donut; you can be aware of the edges of an object, but not the middle. During dissolution, if you try to notice fine detail within the body, or experience a single sensation clearly, or zoom in on a small area, you will become frustrated. Although zooming in to a point would have been easy at an earlier level of development, at this stage, everything is dissolving and disappearing, hence the name “dissolution.” The observing mind is only able to perceive the passing away of objects rather than their arising. If you are able to let this happen naturally, it will be blissful, but if you fight it, it will be frustrating. The mind is markedly unproductive at this stage. Conversations are difficult and it’s hard to concentrate. Attention is diffuse, often dreamy, and there’s a sense of being out of focus. By the time a thought is recognized, it is already gone.

This happy stupidity does not last long, however, as the dukkha ñanas are coming hard on its heels. We are about to enter the true low point of the cycle, territory so daunting that it has tested the resolve of many a yogi.

2.4.6. The Dukkha Ñanas#

[Ñana (pronounced “nyana”) is a word from the Pali language of ancient India, translated here as (insight knowledge).]

The next five insight knowledges together form the most difficult part of the Progress of Insight cycle. They are collectively called the dukkha ñanas, the insight knowledges of suffering. I also refer to them as the dark night of the soul, after the poem by 16th Century Spanish Christian mystic Saint John of the Cross, which describes his own spiritual crisis while practicing in a very different context. (The fact that Saint John of the Cross, among others, has described this mental territory in a way that is strikingly similar to Buddhist descriptions is evidence for a developmental process the potential for which is built-in to human beings, cutting across time spans, traditions, and individuals.)

It makes sense to group the five difficult stages of the progress of insight together as the dukkha ñanas because not every meditator is able to distinguish the individual stages while going through them. Although the Progress of Insight map describes a very particular sequence of unpleasant experiences, many people just experience it as one big blob of suffering while going through the cycle for the first time or even after having gone through it many times. It is not necessary to recognize each of the stages within the dukkha ñanas in order to make progress. It is, however, important to understand that you are highly likely to encounter difficult territory at some point. This is the value of seeing the stages laid out as a graph; meditation does not simply lead to a linear increase in happiness, and understanding this ahead of time can save a great deal of confusion. Forewarned is forearmed, and with a reasonable idea of what to expect as your own process unfolds, you will be better prepared to deal with difficulty as it arises.

2.4.6.1. Knowledge of Fear (Stage 6)#

The name says it all. Following the peak experience of the fourth ñana, the Arising and Passing Away of Phenomena, our meditator’s world began to dissolve. But this was not a problem for her, as the deep joy of the crest of the wave was smoothly replaced by cool bliss. Delicious tingling sensations ran down the arms and legs and thoughts disappeared before they could become the objects of obsession. Now, with the onset of the 6th ñana, Knowledge of Fear, all of that changes. The dissolution of thoughts and physical sensations continues, but the meditator now interprets it very differently; she is terrified to see her world falling apart.

About two weeks into my first three-month retreat at Insight Meditation Society in Massachusetts in 1991, having already experienced the high of the A&P (4th ñana) and the bliss of Knowledge of Dissolution (5th ñana), I was passing the time before lunch by doing walking meditation on the ancient, no-longer-used bowling alley of the former manor house when I was overcome by a wave of abject terror. The hardwood floor of the bowling alley no longer felt solid beneath my stockinged feet. The stark colors of the floor and walls punished my eyes and the walls themselves seemed to writhe and twist as I watched them. I pushed my hand against the wall beside me, seeking something solid. The wall felt spongy. I fell to my knees on the hardwood floor, oblivious to other yogis who may have been passing by, and pushed my fingertips against the oak floor boards, desperate to find something solid. My fingers seemed to sink into the floor. Tears streamed down my face and tapped onto the wooden floor as I found myself overcome by an unspeakable dread that I could not understand.

This experience, which lasted about ten minutes, was my first full-blown taste of the sixth insight knowledge, Knowledge of Fear. As intense as it was, momentarily plunging me into what seemed like a bad acid trip from a 1960s anti-drug propaganda film, it was mercifully brief and passed cleanly away by early afternoon.

A traditional description of the sixth ñana describes a mother who has just seen her husband and all but one of her sons executed. As her only surviving son prepares to suffer the same fate, the dread that his mother feels is akin to the dread of a yogi who attains to the sixth ñana. Personally, I find this story a bit over the top, but it certainly gets one’s attention. And while Knowledge of Fear can indeed be intense, as it was for me, for some yogis it is not spectacular at all, just unpleasant.

2.4.6.2. Knowledge of Misery (Stage 7)#

The next insight knowledge to arise, the aptly named Knowledge of Misery, is number seven of the 16 insight knowledges (ñanas). The body writhes, the skin feels like it is crawling with bugs, and the muscles of the neck and jaw contract unpleasantly, pulling the face into a rictus. It is hard to sit still on the meditation cushion, as the whole body feels unsettled. Unpleasant sensations arise quickly and pass away before the meditator can focus on them, thus taking away one of the strategies that has served her well until now, that of focusing on unpleasant body sensations in order to become concentrated. The experiences I have listed are just some of the many possible ways in which misery can arise. Each individual will have a unique experience. The seventh ñana will not last long, perhaps not more than a day or two, if that.

2.4.6.3. Knowledge of Disgust (Stage 8)#

The ancient ñana-naming commission once again scores a direct hit; the eighth insight knowledge, Knowledge of Disgust is just as it sounds. Food is repellant, the thought of sex is nauseating, and everyone smells bad. The nose may wrinkle up as it if noticing and unpleasant odor. Again, this ñana is generally short-lived.

2.4.6.4. Knowledge of Desire for Deliverance (Stage 9)#

Do you know what it feels like when you are sobbing, completely at wit’s end, overcome by grief and self-pity? The body shakes and rocks, and you feel the release of total surrender to your emotional pain. This is one way the ninth insight knowledge (9th ñana), Knowledge of Desire for Deliverance, can manifest. One way or the other, though, Desire for deliverance is just what the name says: you want out. Out of this situation, out of this experience, even out of this life. There is a pervasive sadness, and a feeling of hopelessness. Most of all, there is aversion. But it doesn’t last long and next in line is…

2.4.6.5. Knowledge of Re-Observation (Stage 10)#

This is where the ancient Buddhist namers of ñanas fell down on the job. The innocuous-sounding Knowledge of Re-Observation, tenth of the sixteen insight knowledges, is a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Books have been written about it. It is the stuff legends are made of. A better name might be Knowledge of Instability. This is the Dark Night of the Soul, and the Agony in the Garden. Although some yogis are able to pass through this stage relatively unscathed, it is common for a yogi’s life to be completely disrupted by the tenth ñana. It is the phase referred to in Zen as the “rolling up of the mat,” because the yogi has the intuitive sense that meditation is only adding to his misery, and abandons the sitting practice. The 10th ñana is St. John of the Cross’ Dark Night of the Soul, a realm of such gut-wrenching despair that the yogi may want to abandon all worldly (and otherworldly) pursuits, pull down the shades, roll up into a ball and die. In more modern terms, the 10th ñana can be indistinguishable from clinical depression.

Although all of the ñanas (insight knowledges) numbered six through eight are included in the dukkha ñanas, it is the 10th that causes the real hardship, as the Re-Observation stage is an iterative rehash of the Insight Knowledges of Fear, Misery, Disgust, and Desire for Deliverance, along with some nasty surprises all its own.

When the yogi attains to the crest of the wave in the fourth ñana, she believes that she has arrived at her destination. From here on in, she reasons, life should be a breeze. Even if she has been warned, she does not believe the warnings. She is completely unprepared for what is to come and is blindsided by the fury of the tenth ñana, which consists of the four previous ñanas of fear, misery, disgust, and desire for deliverance repeating themselves in a seemingly endless loop, and worse with each iteration. In addition, the strong concentration of the fourth ñana (the A&P) seems to have disappeared; one cannot escape into a pleasantly concentrated state, and there is no respite from the unpleasantness and negativity that flood the body and mind.

Actually, the yogi’s practice is even more concentrated than before, but she is accessing unstable strata of mind that are not conducive to restful mind states or happy thoughts. She obsesses about her progress, is sure that she is back-sliding, and devises all manner of strategies to “get back” what she has lost. The meditation teacher tries to reassure the meditator that she is still on track, but to no avail. The best approach at this point is to come clean with the yogi, lay the map on the table, and say “You are here. I know it isn’t easy, but it does not last forever. If you continue to practice, you will see through these unpleasant phenomena, just as you have seen through every phenomenon that has presented itself so far. You are here because you are a successful yogi, not because you are a failure. Let the momentum of your practice carry you as you continue to sit and walk and apply the vipassana technique.”

It is interesting to note that a yogi who is well-versed in jhana (pleasant states made possible by high levels of concentration) may navigate this territory more comfortably than a “dry vipassana” yogi, as concentration is the juice that can lubricate the practice.

The pre-4th ñana yogi who repeatedly fails to penetrate the object and proceed to the Arising and Passing Away of Phenomena is what Sayadaw U Pandita calls the “chronic yogi.” This yogi can go to retreat after retreat, over a period of years, and never understand what vipassana practice is all about. He will, upon hitting the cushion, quickly enter into a pleasant, hypnogogic state, maybe even discover jhana, but go nowhere with regard to the insight knowledges. U Pandita’s frequent exhortations to greater effort and meticulous attention to detail in noting the objects of awareness are aimed at this “chronic yogi.”

The “dark night yogi,” on the other hand, is Bill Hamilton’s “chronic achiever.” Having sailed through the all-important fourth ñana and subsequent ñanas five through nine, he hits a wall at the tenth, and can easily spend years there. But even the darkest night ends, and when it does, dawn is sure to follow. The next stop on the Progress of Insight, Knowledge of Equanimity, will make everything that came before it seem worthwhile.

2.4.7. Knowledge of Equanimity (Stage 11)#

The narrative of the ñanas continues with the 11th ñana, Knowledge of Equanimity. The equanimity ñana is generally a very happy time for a yogi. Having suffered through the solid physical pain of the third ñana and having endured the dark night of the tenth ñana, the yogi wakes up one day to find that everything is just fine. Dissolution of mind and body continue, but it is no longer a problem. In fact, nothing is a problem.

Compared with most of the other insight knowledge phases, the equanimity ñana is particularly vast and complex, so it’s useful to divide it three sections. We’ll discuss it in terms of low, mid, and high equanimity, each with its characteristic sign posts and challenges.

2.4.7.1. Low Equanimity#

I mentioned earlier that the third and tenth ñanas are the only places where a yogi gets hung up. I should perhaps include the early and middle stages of the eleventh on that list. In early equanimity, a meditator can get stalled-out here for lack of motivation. When everything feels fine, there seems little reason to meditate. Many of us are motivated to practice by our own suffering. And since there is very little suffering in the equanimity phase, it is tempting to stop meditating and enjoy the passing parade. The challenge, then, in early equanimity, is simply to keep meditating, whether you feel like it or not.

A typical pattern that I have seen repeated in dozens of meditators is this: shortly after attaining to the 11th ñana and feeling a great deal of relief from suffering, especially as contrasted with the difficulties of the dark night phase, the yogi becomes complacent and stops practicing regularly. Someone who has maintained a regular practice of an hour or more of formal sitting per days for months suddenly finds himself sitting sporadically, perhaps two or three times a week, and even then for less time than usual. The predictable consequence of this reduction in practice is to fall back into the dukkha ñanas, at which point the yogi, once again motivated by suffering, resumes a rigorous practice schedule, returns to low equanimity, feels relief, stops practicing again, and falls back into the dukkha ñanas. And so on. There is no theoretical limit to how many times this can happen. Sooner or later, the yogi figures it out; the key is to make a firm resolution to keep practicing systematically until stream entry, no matter what.

2.4.7.2. Mid Equanimity#

Back on a regular practice schedule, it doesn’t take long for our model meditator to pass from low equanimity to mid equanimity. At this stage, the challenge is slippery mind. By slippery mind, I mean an inability to stay focused on one object, and a tendency to drift into pleasant reverie. At first, this isn’t even noticeable to the meditator as she is having so much fun feeling calm and free. After a while, though, slippery mind becomes maddening; even if the meditator makes a firm resolution to stay with her objects of meditation (in choiceless vipassana, the objects of meditation are the changing phenomena of mind and body as they spontaneously arise), another random thought train has slipped in the back door almost before she has finished making the resolution. Slippery mind is a natural consequence of a mind that is unusually quick and nimble, together with the fact that the equanimity ñana is still part of the dissolution process. In the first stage of dissolution, the fifth ñana (Knowledge of Dissolution), the focus was on the passing away of gross physical sensations, so it was experienced as blissful. In the middle stages of dissolution, the dukkha ñanas (numbers 6-10), the mind itself was seen to be dissolving, along with the physical world and even one’s own sense of identity. The fear and grief induced by the loss of the apparent self were mind-shattering. Now, in the eleventh ñana, Knowlege of Equanimity, the yogi has entered the final stages of dissolution. Even the fear and grief are seen to disappear as soon as they arise. Things are as they are, and life is good. But the yogi will have to relearn the art of concentration.

One way to understand what is happening here is to hearken back to the phases of chicken herding. In order to master the equanimity ñana, the yogi has to completely develop the fifth and final phase of chicken herding. In this phase, the chicken herder has become one with the flock and is aware of the entire barnyard all at once. This takes a great deal of momentum, and a great deal of practice, because you can’t “do” this as much as you can “allow” it; the latter phases of concentration arise naturally when the momentum is strong. And in order to have momentum, you must practice. Frustrated by her slippery mind, however, the yogi may try to hold the objects of meditation too tightly. This will not work with slippery mind. Holding tightly will not allow the later phases of concentration to develop, and will result in yet more frustration.

This is a good place to mention wandering mind and its relationship to concentration. It is the nature of the mind to wander, and even advanced meditators have to deal with this phenomenon. Wandering mind cannot be defeated through brute force, but it can be managed. I once had a beginning meditation student tell me that she had just finished a sitting in which she thought about her kids, her husband, the shopping, her job, and the fact that she was never going to be good at meditation.

“Excellent,” I told her. “Just meditate in between all of that.”

There is no point in trying to will your mind to silence by brute force, because the effort to do so will make you even more agitated. Instead, cultivate concentration (the ability to sustain attention on an object with minimal distraction) a little bit at a time, in the same way that you would build a muscle by exercising it. As the concentration muscle gets stronger, you’ll be able to sustain it for ever longer periods of time. Since the developmental process of awakening is dynamic, it’s unavoidable that you will have to relearn concentration skills at various times along the way; every time your perceptual threshold changes, you gain the ability to notice phenomena you couldn’t see before. This is a double-edged sword; life is richer and more interesting, but there is also more potential for distraction. This potential for distraction has to be balanced by corresponding increases in your skill at concentration, which set the stage for yet another change in perceptual threshold, and so on. Think of it as an ongoing process rather than a discrete goal with a fixed end point, and be prepared to keep pushing this edge of development throughout your life.

During any meditation sitting, there are moments when the monkey-mind slows down enough that it’s possible to stay with an object for a few moments, whether the object is the breath, a kasina object, or whatever it may be. Those few moments of concentration condition the mind in such a way that there is a little less time before the next window of calm appears in between the passing storms of monkey-mind. This momentum, or snowball effect, where each little bit of calm conditions the next moment of calm, is an important principle in Buddhist meditation. In traditional teachings, the Buddhists identify “proximate causes” for various mental factors. For example, the proximate cause for metta (lovingkindness) is seeing goodness or “loveableness” in another person. The proximate cause for mudita (sympathetic joy at the good fortune of another) is seeing another’s success. And the proximate cause for concentration is none other than… concentration! With this in mind, it is easy to see how important the snowball effect is when you are trying to steady the mind. And from this point of view, there is no reason to feel frustrated even when an entire sitting goes by with just a few brief windows of calm. Every moment of concentration makes it more likely that the next moment of concentration will arise. Always keep in mind that it’s all right that you haven’t mastered this yet; you can learn, you can get better. It’s a process. Awakening itself is the developmental process of learning to see experience as process. And awakening, by this definition, is the crown jewel in the collection of skills, understandings, and developments that, taken together, are contemplative fitness.

Wandering mind, then, becomes ever more manageable with practice, and this is good because the later phases of concentration (chicken herding 4 and 5) will not arise if the mind is not still. This does not mean that thinking stops during deep concentration, but rather that it fades into the background, slows down, and does not pull the mind away from its intended target, i.e., the object or objects of meditation. When you are firmly abiding in a jhana and thinking arises, it is felt as subtle physical pain as it begins to pull you out of your pleasant state. With practice, this pain becomes a familiar signal that it’s time to turn the mind away from thoughts and toward the object of meditation… or face the consequences. The consequences are simply that you unceremoniously exit the jhana. The skill to exit a jhana according to the schedule you decided upon before entering the jhana as opposed to staying too long or being dumped out prematurely is, as we discussed earlier, the fourth parameter for mastery of a jhana.

So, how does the yogi get to equanimity in the first place? Why do some people get hung up for years in the preceding ñana? The key to coming to terms with the tenth ñana, Knowledge of Re-observation, is surrender. Once the yogi surrenders to whatever her practice brings, she is free. Having surrendered, it does not matter whether the present experience goes or stays, or whether it is pleasant or unpleasant. It is this attitude of surrender, along with time on the cushion, that results in the full development of the strata of mind where fear, misery, and disgust live. Once those mental strata are developed, or (viewed through another lens) once the kundalini energy is able to move freely through those chakras, it is as if a groove has been worn through that territory. You now own that territory and although you move up and down through those same mental strata every day and in each meditation session, they no longer create problems in your meditation.

When it becomes obvious that slippery mind is the only thing standing between you and further progress, there is a specific remedy that you can apply. The trick is to target thoughts directly. Here are some effective ways to do this:

Turn toward your thoughts as though addressing another person, and say, “Speak! I am listening.” Try it now. Notice how thought suddenly has nothing to say! The mind becomes silent as a church. Do this as many times as you need to until the mind becomes still.

Repeat to yourself silently or aloud, “I wonder what my next thought will be.” [This highly effective practice comes from Eckhart Tolle’s The Power of Now.] Watch your mind the way a cat would watch a mousehole, alert to the exact moment the mouse (a thought) peeks its head out of the hole. By directly and continuously objectifying thought in this way, thoughts will subside, leaving blissful silence in the mind.

Note (label) your thoughts carefully. Put each thought into a category. Planning thought, scheming thought, doubting thought, self-congratulatory thought, imaging thought, evaluation thought, self-loathing thought, reflection thought. By objectifying your thoughts directly, you turn them into allies; the thoughts themselves become the object of your meditation rather than a problem.

Count your thoughts. By counting them, you have again made thoughts the object of your meditation. Thoughts are only a problem when they are flying under the radar. Light them up with attention and they cease to cause trouble.

Do a binary note (a noting practice that has just two choices) of “thinking/not thinking” or “noisy/quiet.”

Always think in terms of co-opting your enemies. Anything that seems to be a hindrance in your practice should immediately be taken as the object of your meditation. In this way, you turn the former hindrance into an ally in your process of awakening.

2.4.7.3. High Equanimity#

Once thoughts have been clearly objectified and are no longer flying under the radar, high equanimity naturally emerges. At this stage, sitting is effortless. The yogi can sit happily for hours at a time. If pain comes, no problem. Wandering mind, no problem. Objects present themselves to the mind one after another, obediently posing for inspection. This is where the yogi really gets a feel for what vipassana is all about, as she effortlessly deconstructs each thought and sensation that appears. In high equanimity, the mind is unwilling to reach out to any object. It doesn’t move toward pleasant objects or away from unpleasant objects. This is what makes it possible to sit for long periods of time; when pleasant is not favored over unpleasant, there is no particular reason to get up.

The mind state of equanimity is inherently appealing. On a hierarchy of desirable states, joy is higher than exhilaration, bliss is higher than joy, and equanimity is higher than bliss. Viewed through this understanding, it’s easy to see the natural logic in how the Progress of Insight unfolds; notwithstanding the occasional rough patches in the 3rd ñana and the dukkha ñanas, the progression has moved from the quiet exhilaration of the 1st ñana through the joy of the 4th, the bliss of the 5th, and has finally stabilized in the equanimity of the 11th. From my point of view as a teacher and coach, it’s interesting to track the hours of formal sitting as a yogi develops through the three phases of equanimity. When she gets to high equanimity, the hours will usually spike up. A meditator who has been struggling to find time in her busy life for two hours of daily meditation may suddenly find herself sitting three, four, or even five hours a day. Who knows where all these extra hours come from? People will give up television, reading, time with friends. They’ll sleep less and take less time eating than usual or leave aside habitual tasks that don’t really need to be done. When I ask why they are sitting so much now, students reply that there isn’t anything else they’d rather do. They just feel like meditating. This spike in practice hours is phase-specific and usually only lasts a few days or weeks. It ends when the yogi reaches stream entry (or the path moment of whichever cycle they happen to be working through at the moment), at which time their practice hours fall back to a more sustainable pace. Whenever I see a yogi’s practice hours spike in this way, I feel confident that they are about to complete a path and I tell them so. This particular trick of prognostication has proven remarkably accurate and I marvel every time this process unfolds as predicted by a 2,000 year-old map of human development.

2.4.8. Path and Fruition#

Let’s briefly review what we’ve seen so far:

Theravada Buddhism identifies Four Paths of enlightenment. The first of these Four Paths can be subdivided into 16 “insight knowledges” or ñanas. These ñanas arise one after the other, in invariable order, as a result of vipassana meditation (objectifying, investigating, and deconstructing the changing phenomena of mind and body). Most of the heavy lifting is done in the first three ñanas; taken together, the first three insight knowledges can be thought of as the pre-vipassana phase. During this first phase of practice, it’s as though the yogi is rubbing two sticks together in an effort to start a fire.[Thanks to Shinzen Young for this image of rubbing two sticks together to start a fire, thereby releasing the potential energy contained in the wooden sticks.] When the fire takes hold in earnest, the 4th ñana, the all-important Arising and Passing of Phenomena (A&P) has been attained. From this point on, the practice is more about constancy than heroics. Patience and trust are important; at times it is necessary to avoid the temptation to push too hard, understanding that just as you can’t force a young plant to grow by pulling on its stalk, you can’t force yourself to develop through the ñanas.

My hypothesis is that this process of development is hardwired into the human organism. Everyone has the potential to develop along this particular axis, and in order to do so one must simply follow the instructions for accessing and deconstructing each new layer of mind as it arises.

2.4.8.1. Stages 12-16#

We now continue to track the progress of our idealized yogi. It’s tempting to make a big deal out of the Path moment (the moment in which stream entry is attained). So much emphasis is put on attaining stream entry that we imagine there is some secret to it; surely there is some special bit of knowledge or some extra bit of effort required to “get us over this last hump.” In fact, it’s not like that at all. Just as all the previous insight knowledges arose, in order, on cue, the Path moment shows up out of nowhere when you least expect it. It’s a little bit like chewing and swallowing; when you put food into your mouth, you begin to chew. At some point, when sufficient chewing has taken place, you swallow. It’s an involuntary reflex. You don’t have to obsess about whether swallowing will occur or try to control the process. If you do, chances are you will just get in the way. Similarly, when you meditate according to the instructions, the various strata of mind are automatically accessed, the apparently solid phenomena are automatically deconstructed, the information is naturally processed, and you automatically move from one insight knowledge to the next without having to orchestrate the process at all. In just this way, our yogi is sitting there one day (or walking, or standing), and there is a momentary discontinuity in her stream of consciousness. It’s not a big deal. But, immediately afterward, she asks herself, “Was that it?” It seems that something has changed, but it’s very subtle. She feels lighter than before. Maybe she begins to laugh. “Was that it? Ha! I thought it was going to be a big deal. That was hardly anything. And yet…”

Something is somehow different. It would be very difficult to say exactly what. In many ways, things feel exactly the same.

In Mahasi Sayadaw’s classic The Progress of Insight, he explains that insight knowledges 12-16 happen all together, in a single instant. Stages 12-15 are one-time events signaling stream entry, while stage 16, fruition, can be re-experienced later as many times as desired. Mahasi’s descriptions, based on the 5th Century Buddhist commentary the Vissudhimagga (Path of Purification), itself based on an even earlier text, the Vimuddhimagga, are interesting and well worth the read.[http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/mahasi/progress.html#ch7.17] From the point of view of the yogi, however, it’s much simpler; she develops through the first eleven insight knowledges and then something changes in her practice, completing the Progress of Insight. From a simple, subjective point of view, then, there are just twelve stages: the first eleven, including equanimity, and the Path and Fruition event, which somehow resets the clock and completes the cycle. Fruition is technically the 16th insight knowledge, and we’ll preserve that numbering system, although I will gloss over insight knowledges 12-15, understanding them as theoretical structures intended to explain changes the yogi will notice after the fact as opposed to discrete stages the yogi experiences is real time as they occur. In fact, the yogi, by definition, experiences nothing whatsoever during the momentary blip that is the Path and Fruition moment.

Later, as the days and weeks go by, it becomes more and more clear that the event was indeed First Path (stream entry). First of all, the practice is different now. Instead of having to sit for 10 or 15 minutes in order to work herself up to the 4th ñana, every sitting begins with the 4th ñana or A&P. From there, it takes only a short time, sometimes a few minutes, sometimes just seconds, to get to equanimity.

Second, our yogi may suddenly find that she has access to four or more clearly delineated jhanas, or “realms of absorption.” She may find that she can navigate these states simply by inclining her mind toward them, jumping between them and manipulating them at the speed of thought.

Third, there is the possibility of re-experiencing the 16th ñana, Knowledge of Frution; a yogi can learn to call up fruition, which, in classical terms, is said to be the direct apprehension of nibbana (nirvana), at will. There are said to be three doors to nibbana, namely the dukkha (suffering), anicca (impermanence), and anatta (no-self) doors. Each of these modes of accessing cessation leads to a slightly different experience of entering and exiting nibbana. The fascinating exploration known as fruition practice is only available to post-stream entry yogis and consists of systematically calling up, becoming familiar with, and comparing these phenomena.