The Path to Nibbāna#

Note

Other formats (PDF, HTML, ePub) available from github.com/edhamma/jodok-path.

This file was build on Nov 19, 2024, rev. 0.1 / git b066528 of the source.

Contents#

Front#

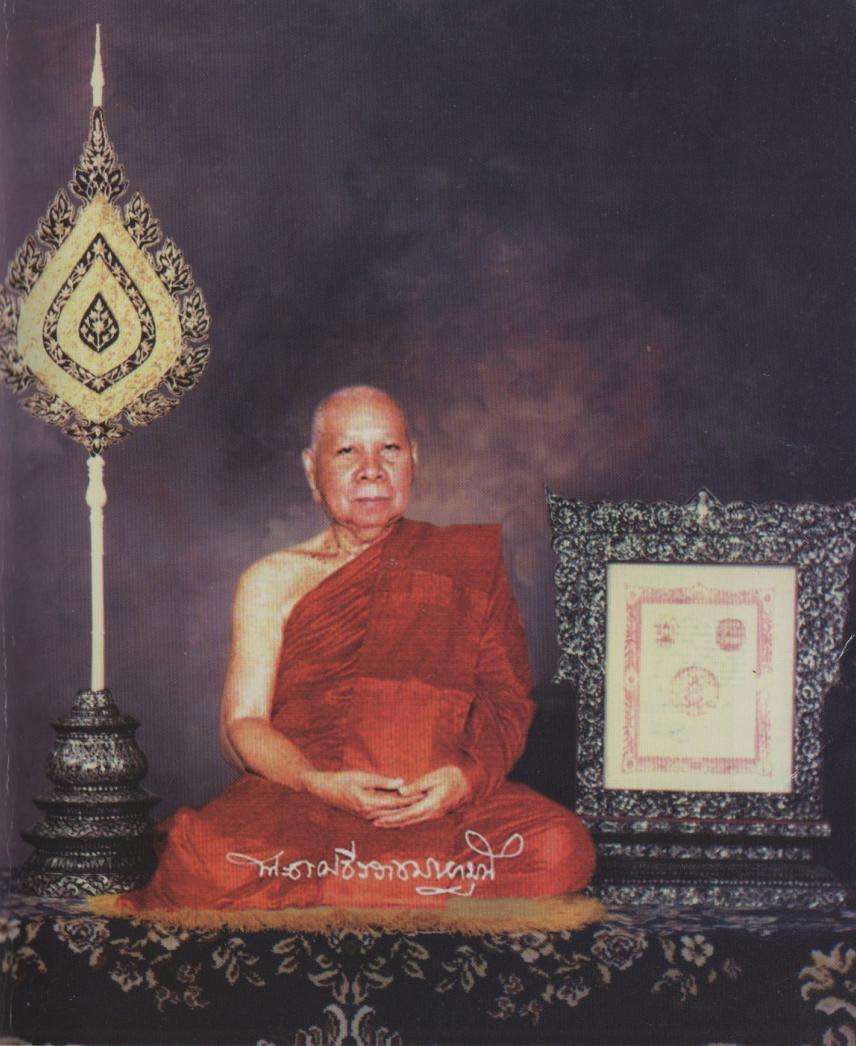

The Ven. Phra Dhamma Theerarach Mahamuni#

พระธรรมธีรราชมหามุนี (โชดก ญาณสิทฺธิเถร ส.ธ.๙)

พระอาจารย์าใหญ่ฝ่ายวิปัสสนาธุระ

Electronic edition notice

In a few places, obvious erros of the print were corrected. Footnotes with Pali locations were added. Spelling of Pali words was left intact.

Foreword to the English Translation#

The path to Nirvana, which you are holding in your hands, is translated from “The Path to Nirvava- Thai version -. It is a directt ranaslation of the original book of the Ven. Phra Dhamma Threerarach Maharnuni (Jodok Yannasit). The content of this book is emphasized to the Insight Vipassana method handbook,including the evaluation of meditation as The Discourse of Four Foundations of Mindfulness and the result of insight meditation. The path to Nirvana is suitable for all people who would like to understand, get inside and develop their mind. The wisdom and peace from meditation will encourage family, society, nation, religion and then make the peaceful world.

This book has been published in 8 editions, during various occasions. This edition is the 9th, the English publishing for each edition is on behalf of the burden of contemplation division, Vipassana Center, where the Center of Buddhist propagation. This international Vipassana Center has been supported by The Ven. Phra Dhamma Threerarach Mahamuni (Jodok Yannasit), who is the former abbot of Mahadhatu Monsatery, and the Ven. Somdet buddahchan (Art Asapathera).

Translator’s Introduction#

This book is the work of the late Ven. Phra Dhamma Theerarach Mahamuni Mahāthera, the late head of the meditation masters in Thailand, who passed away on the 30th of June 1988.

While he was alive he taught meditation to both Thais and foreigners in Thailand and throughout the world. The Vipassana Centre at Wat Mahadhatu considers that “the Path to Nibbana” is one of the most useful of his books for meditators and those who are interested in meditation. This book covers both theory and practical exercises. So the Vipassana Centre at Section 5, Wat Mahadhatu has decided to reprint this book, to be used as a guide to help those who are interested in Vipassana meditation.

There are three parts to this book. Part 1 is theory. Part 2 is exercises for meditation practice and part 3 is a manual for checking you Vipassana progress.

We hope that this book will prove useful for those who are interested in practising meditation. It can be used as a guide for beginners, but the book alone is not enough, it should be used as additional guidance when practising with a meditation teacher. Those who have extensive experience should consult a meditation master.

We sincerely hope you make progress in your meditation practice.

Foreword to the 3rd Edition#

Dhammo have rakkhati dhaṃmacāriṃ chattaṃ mahanthaṃ viya vassakāle. [1]

The Dhamma shelters the Dhamma-followers like a Great umbrella in the rainy season.

The Principal Teaching of Lord Buddha comprises three categories: The Study of the Scriptures (Pariyatti Dhamma), the Practice of the Dhamma (Patipatti-Dhamma), and Realization (Pativedha-Dhamma). They depend upon each other. Then they can develop Buddhism in the future.

The Study of the Scriptures refers to the study of the Tipitaka, the Three Collections of the Buddha’s Teaching in which are contained morality (Sila), concentration (Samadhti) and Wisdom (Paññā).

The Practice of the Dhamma is directed towards training in and development of ethical conduct, concentration of mind and intuitive wisdom through the system of Budhist Meditation.

The Stage of Realization being the result of the practice, brings about Enlightenment and Complete Freedom from all forms of mental defilements. This is termed, “Realization” according to the Buddhist sense and aim of life.

The Study of the Scriptures is like a whole coconut.

The Practice of the Dhamma is like breaking a coconut.

The stage of Realizations is like breaking a coconut and eating all its contents.

All followers should cultivate these three stages so that they will have peace and happiness in present and future lives.

May they all attain the happiness of Nibbana.

1. The Path#

1.1. (Path)#

In Buddhist tradition the term “Path” has two senses, one being “Pakati maggo” or an ordinary path, i.e. a byway for men and animals, and another “Patipadā maggo” or the path of good or bad behaviour for men alone, traversed through deeds, words and thoughts.

Patipadā maggo is divided into five kinds:

The Descending Path, brought about by offences against the normal Code, and based on Greed, Hatred and Delusion.

The Human path, the path of five moralities or the 10-fold wholesome course of action (Kusala-Kamma-Patha).

The Path to the Six Classes of Heaven, which comprises eight classes of moral consciousness, culminating in Moral Shame (Hiri) and Moral Dread (Ottappa), resulting in alms-giving, attending sermons, building chapels, temples, ecclesiastical schools, hospitals and ordinary schools.

The Path to the Abode of Brahma which is the development of tranquility of mind (Samatha bhavana) by means of meditation upon any of the forty traditional subjects; very briefly, these are classified technically as the ten “Kasina” (Contemplation devices), ten “Asubhas” (Impurities), ten Anussatis“ (Reflections), four ”Brahma-Vihāras“ (Sublime States), one ”Ahārepatikūlasaññ a“ (Reflection one the loathsomeness of food), one ”Catudhātu Vavatthāna“ (Analysis of the four elements), and four ”Arupakammatthāna“ (Stages of arūpa-jhāna).

The Path to Nibbāna, Pali; (Sanskrit:Nirvāna), which is the development of Insight (Vipassana bhavana), having Nāmarūpa, or mental and physical states, as the objects of meditation. Of these five paths, the fifth is the one under consideration and is known as “ekāyana magga” (The Only Way). It is so called because of the following qualities:

It is a straight path, never branching into byways.

It is the path for a person who leaves society and retires into a secluded place to practise.

It is the path of the Buddha himself, as He was the discoverer of this path by his own effort.

It is a path found in Buddhism only, and not explicitly in other religions.

It is the path leading to Nibbāna, as set out in the Pali Scriptures:

“Cattārome bhikkhave satipatthānā bhavitā bahulikata ekantanibbitāya virāgāya nirothāya upasamāya abhiññaya sambodhaya nibbanāya samvattati”

“Brethren! These four Foundations of Mindfulness, (Satipatthānā), when fully practised, produce detachment, freedom from craving, complete release, perfect bliss, perfect wisdom, enlightenment, Nibbāna.”

“Seyyathāpi bhikkhave gamganadipācinaninnā pācinaponā pācinapabbharā evameva kho bhikkhave cattāro satipatthāne bhavento satipatthāne bahulikarōnto nibbānaninno hoti nibbānapono nibbānapabbhāro.”

“Brethren! As the Ganges flows, rushes and races towards the West, so does a bhikkhu who develops and practises the Four Foundations of Mindfulness tend towards Nibbāna.”

1.2. Questions and Answers#

Q. Where and when do the five Aggregates (Khandha) of the present moment, which are reducible to matter and mind (rūpa dhamma and nama dhamma) arise and cease?

A. They arise at the six internal sense-bases (āyatana), namely: eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body and mind-base, and at the six external sense-bases : visible object, sound, odour, taste, body-impression and mind object, whenever one’s eyes see a form, ears hear a sound, nose senses a smell, tongue experiences a taste, body contacts something cold, hot, soft, or hard, or one’s mind seizes upon an idea; and they cease whence they arise, being born and perishing instantly.

Q. Whence and when do greed, hatred and delusion arise and cease?

A. They also arise at the internal and external sense-bases, for example, when one’s eyes see a form, grasping at it is greed (lobha) and hatred (dosa)“ lack of mindfulness in acknowledging the reality behind the form is unawareness. The same applies to the other kinds of perception.

Q. While greed, hatred and delusion can still arise, can Man be free from the Descending Path?

A. He cannot.

Q. If that is so, what can one do to avoid the Descending Path?

A. One has to carry out the path to Nibbāna.

Q. What is the path to Nibbāna?

A. It is based on the Four Foundations of Mindfulness by means of Insight Meditation (Vipassanā Bhavanā):

Contemplation of the Body (Kāyānupassana),

Contemplation of Feelings (Vedanānupassanā),

Contemplation of States of Consciousness (Cittanupassanā),

Contemplation of Mind-objects (Dhammānupassanā).

During the Buddha’s Ministry, while the Exalted One stayed at a village called Kammasadamma in the state of Kuru, He mentioned the people of Kuru as the inspirers of His talk and thereupon gave a sermon on the practice of the Foundations of Mindfulness, which will be condensed below.

(The people of Kuru state, no matter whether they were Bhikkhus, Bhikkhunis or lay disciples were of quick understanding as their environment and social conditions were good, and all of them possessed healthy bodies and minds suitable for deep Contemplation. Knowing this, and having a gathering of the Kuru people before Him. Lord Buddha at once delivered the profound sermon, on the Four Foundations of Mindfulness, to them.)

The Kuru followers of Buddhism used to practise the Foundations of Mindfulness regularly. Even the slave labourers talked to one another on the Foundations of Mindfulness. At the waterfronts or the workshops, or wherever else they happened to be, they all discussed this subject. Whenever any person was asked which one of the four Foundations he has been practising, if he answered he had not, the others would reprove him by saying’ that, though he was alive he was really behaving as if dead. They would exhort him not to be negligent and instruct him to practise one of the Foundations of Mindfulness. Should the person addressed answer that he had been practising one of the Foundations of Mindfulness, the Kuru people would praise him three times with the words, “That is good” and commend him for living an excellent life and achieving conduct worthy of a human being, the Buddha having been bom into the world for the benefit of such as he. Considering that we have encountered Buddhism, it is therefore appropriate that all of us should practise the Dhammas of liberation without letting the time go by uselessly. If we have done great merit in the past, we shall be able to obtain Path and Fruition according to our latent disposition, as set out in the following:

“Ekadhammo bhikkhave bhāvito bahulikato Sotāpattiphalasacchikiriyāya samvattati sakadāgamiphalasac-chikiriyāya samvattati,”

meaning, “Brethren! This incomparable Dhamma, practised fully by any person, would result in Sotāpattiphala, Skādagāmiphala, Anāgāmiphala, and Arahattaphala. What is this incomparable Dhamma? It is Kāyagatāsati, Mindfulness of the Body.”

“Amatante bhikkahave na paribhuñjanti ye Kāyagatasatim na paribhuñjanti amatante bhikkhave paribhuñjanti ye Kāyagatasatim paribhuñjanti,”

“Brethren! Those who do not practise mindfulness of the body, will never taste immortality; those who so practise mindfulness of the body, will certainly enter into immortality.”

Q. Are there any preparations which the practitioner should make beforehand?

A. Certain necessary conditions are :

To live near a capable instructor.

To keep the six guiding-faculties (indriya) healthy.

To keep the mind fixed upon the Four Foundations.

Duties to be performed by the practitioner :-

Make a positive resolution that one will not be discouraged as long as one has not yet attained the exalted Dhamma through great effort, diligence and perseverance.

Eat less, sleep less and speak less, but practise more.

Control one’s eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body and mind

Perform all actioas slowly and with constant awareness.

Perform all actions under the guidance of the following three healthy mental components, energy, mindfulness and awareness. The practitioner should endeavour to walk mindfully and to acknowledge the various perceptions without wishing to discontinue. This is the arousing of energy. Acknowledge every movement beforehand. This is the practice of mindfulness. When performing even the least of actions be conscious of every movement. This is the development of awareness.

Activities to be avoided by the practitioner.

Busying oneself with various jobs, such as cleaning, writing, and reading.

Indulging in much sleep with consequent loss of effort. The practitioner should sleep at the most four hours a day.

Indulging in talking and searching after friends, thus losing one’s practice of mindfulness.

Seeking company.

Lacking restraint of the senses.

Immoderation in eating. The proper course is to stop eating when five more mouthfuls would prove sufficient.

Failing to acknowledge mental activity when the mind seizes on or loses hold of an idea.

When the mind is concentrated :

Walk mindfully for one hour, then sit down and acknowledge the various trends of body and mind as they arise, increasing the time for this practice form thirty minutes to one hour or more according to one’s capability.

Here is must be said in warning that if the energy exerted is great while the concentration is insufficient, distraction will arise. For example, when one acknowledges one’s awareness, “Rising,” “falling,” “sitting,” “touching,” if one cannot acknowledge the activity at that moment and yet continue, the energy exerted to try to do so will be too great and distraction will arise.

If concentration is too strong while energy is insufficient, apathy and weariness will ensue.

If faith is too great while reason is weak, greed will seize hold of the mind.

If reason is too strong while faith is insufficient, doubt and delusion will result.

And so the practitioner must learn through the practice of mindfulness how to bring about a balance of faith, reason, energy and concentration.

This is the way to bring these faculties or indriyas inbalance:

While practising the walking exercise, do it slowly and acknowledge the various movements at every moment. Your gaze should be about 4 feet in front of you, when looking down however, pain may arise at the back of the neck. If that occurs fix your gaze at a point about two metres in front of your feet. In so doing, one will not lose control of one’s mind and will also attain good concentration in the sitting posture. Truth will then be revealed when the mind has spent a certain period in deep concentration.

After the performance of the mindful walking, begin to acknowledge the rise and fall of the abdomen in the sitting posture. In doing so, do not restrain the mind and body too much or use too much effort. For example, there is a form of over-exertion which arises when one feels sleepy and tries to keep awake, or when one cannot acknowledge the constant changes in one’s mind and body, but still keeps up the effort. One should also never be too slack in practice and allow the mind to act under the sway of various unhealthy tendencies whenever it has the inclination. One should practise according to one’s capacity without too much restraint or effort and without yielding to the power of latent tendencies. This is the Path of Moderation.

Keep one’s mindfulness constant; for example, after performing the mindful walk, acknowledge in the sitting posture every activity of the body and mind without letting mindfulness slip. Do this slowly and without agitation.

Preliminary arrangements and how to begin the practice of Insight Meditation (Vipassana).

The monks should make confession first, while the lay disciples should ask for the precepts before practice. Most of them observe the eight precepts.

Pay homage to the Triple Gem and one’s instructor thus: “Imaham Bhagavā attabhavam Tumhākam pariccajami” “Master, May I pay you homage for the purpose of practising insight meditation (Vipassanā) from this moment!”

Ask for the exercises as follows: “Nibbānassa me bhante sacchikaranatthaya Kammatthānam dehi” “Master, Will you give me instruction for in sight meditation (Vipassana) so that I may comprehend the Path, the Fruition and Nibbāna later?”

Extend your friendship to all beings in some such way as this:

“May I and all beings be happy, free from suffering, free from longing for revenge, free from troubles, difficulties and dangers and be protected from all misfortune. May no being suffer loss! All beings have their own Kamma, have Kamma as origin; have Kamma as heredity; have Kamma as refuge; whatever Kamma one performs be it good or bad, returns to one.

Practise the exercise of mindfulness of death thus: Our lives are transient and death is certain. That being so, we are fortunate to have entered upon the practice of insight meditation (Vipassanā) on this occasion as now we have not been born in vain and have not missed the opportunity to practise the Dhamma.

To the Buddha and his disciples, take a vow, as follows: “The path which all Buddhas, their venerable left-hand and right-hand disciples.their eighty great disciples and their Arahat disciples have taken to Nibbana, the path which is known as the Four Foundations of Mindfulness and is the path comprehended by the wise, I solemnly promise that I will follow in sincerity to attain that Path, the Fruition, and Nibbāana, according to my own initiative from this occasion onwards.”

“May I offer the Buddha this practice of Dhamma worthy of Dhamma!”

“I am certain to cross over suffering from birth, suffering from decay, suffering from diseases and suffering from death by this practice.

The instructor then gives advice to those beginning the practice as he sees fit.

1.3. Advice to the Practitioner#

Now that we have been fortunate enough to meet the Dhamma, the doctrine of the Buddha, it is most appropriate to cultivate the precepts, concentration, and insight in one’s own self to the point of perfection. Those perfect in the precepts are certain to achieve happiness in the present and future lives; nevertheless these precepts are mundane (lokiya-silas) and it is not guaranteed that they can help people to be absolutely free from the descending path. As a result we have to cultivate precepts leading to the supra-mundane, to greater perfection. These are precepts for the attainment of the Path and Fruition. If we practise the exercise up to the precepts for attainment of Fruition, we are certain to be free from the Descending Path. It is, therefore, very advantageous to cultivate the precepts for the Path and Fruition in this life. If we practise the exercise with great carefulness we will be successful, but if we ignore the opportunity to practise, we cannot attain to freedom. On this occasion there still remains an opportunity for the demerits latent from the previous life to become effective, and demerits not yet performed are liable to be performed. Those already performed are liable to accumulate. Every human life is to be considered as having been bom of merits and as a wonderful opportunity.

To enter the practice of Insight Meditation (Vipassana) means the cultivation of such potentialities as perfection and the development of the Precepts, Concentration and Wisdom from the lower to the higher levels. As we have already seen, the precepts fall into two classes: mundane, consisting of the ordinary moral codes for laymen and bhikkhus, and supra-mundane, which are developed only in persons practising Insight Meditation (Vipassana) up to attainment of the Path. Concentration also falls into the same two classes, the mundane concentration of practitioners who have not yet attained the levels of Path and Fruition, and supra-mundane concentration, arising in persons practising Insight Meditation (Vipassana) up to these levels. The same applies to the faculty of Wisdom, mundane wisdom comprising insight into what is meritorious or demeritorious, beneficial or detrimental, profitable or unprofitable, and some understanding of the nature of mental and physical states and the “three characteristics” while supra-mundane or developed wisdom arises in those practising Insight Meditation (Vipassana) up to the levels of the Path, the Fruition and Nibbana.

Those who practise Insight Meditation (Vipassana) do so in order to learn to live a holy disciplined life to the point of perfection. It is, therefore, to be condidered our great advantage, but those who let the opportunity slip by, will realise afterwards that they met with Dhamma in letter only and missed the spirit. However, those who have practised and acquired the eyes of Wisdom will be greatly rewarded and are to be thought of as having paid the only real form of homage to the Buddha. And they are also to be condidered the true disciples of the victorious One, as may be seen from the following quotation: “Bhikkhave mayi sasenho tissasadito va hotu” meaning “Brethren! whoever has love for me, let him be like Tissa. Not those who offer me flowers, incense, candles and all kinds of perfumes are to be considered as having paid me true homage, but those who have practised the Dhamma worthy of Dhamma,”

Also, those who have practised Insight Meditation are to be reckoned as having furthered the cause of Dhamma as set out in Pali:

“Yāva hi ima catasso parisā mam imāya patipatti-pūjāya pūjessanti”, meaning, “For however long the four assemblies pay me homage with this practice of Dhamma, just so song will my religion endure, as even the full moon hangs suspended conspicuously amidst the sky at night”

Those deserving persons who have joined in the practice should be considered as having done enormous benefit to themselves and to others, even including the nation, the faith, the King and the Constitution.

“Vuddhim virulhim vepullam pappotu Buddhasā sane.” “Finally may you all be prosperous, flourishing and fortunate in Dhamma; in other words, may you attain the Path, the Fruition and Nibbhāna.”

Having given such advice, the Instructor should being to give exercises to those entering the practice, thus:

Instruct them to walk mindfully, and to acknowledge the movements in their mind in some such way as “Right moves thus, Left moves thus.” Teach them also to be mindful while standing and turning around.

Instruct them how to concentrate in the sitting position, i.e. to meditate on the rising and falling of the abdomen, acknowledging the movement: “Rising, Falling,” and teach them how to recline in a posture suitable for concentration. (Note of the translator: In meditating on the rising and falling of the abdomen one has to employ what is called in physiology,’ diaphragm breathing which is the sinking in and bulging out of the abdomen in succession. Meanwhile the chest is kept at rest. Diaphragm breathing is employed when the body is at rest and the mind is not to emotional. In the sitting or reclining posture meditate on the rising and falling of the abdomen only, and not oh the passage of air through the nostrils. This kind of diaphragm breathing in itself prevents strong emotions from arising and is a physiological key to the prevention of the various defilements (Kilesa) from entering the mind.)

Instruct them to meditate on various feelings (Vedana) and acknowledge them accordingly. For example, when one is in pain, acknowledge the pain, “Painful, painful,” etc.

Instruct the students to meditate on thought when various ideas arise. For example, when one is thinking, acknowledge the thought (citta) “Thinking, thinking.”

Instruct them to meditate on the six doors of the senses, the eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body and mind, and acknowledge the perceptions thus:

While seeing, acknowledge the sight, “Seeing.”

While hearing acknowledge the sound, “Hearing.”

While smelling, acknowledge the smell, “Smelling.”

While tasting, acknowledge the taste, “Tasting.”

While experiencing a cold, hot, soft or hard touch, acknowledge the touch, “Touching.”

While thinking, acknowledge the thought, “Thinking.” (or imagining)

Instruct the student of Insight Meditation (Vipassana) to meditate on the movements of the body and acknowledge them as described; for example; to step forward, to step backward, to turn right, to turn left, to crouch, to stretch, to hold the begging bowl, to dress, to cover the body with a blanket, to eat, to think, to chew, to taste, to discharge excretion and urine, to walk, to stand, to sit, to lie, to sleep, to wake up, to speak and to keep quiet.

Note

On the first day the instructor should examine those who are beginning the practice. If they know the Doctrine only a trifle or are old people, then he should instruct them to walk mindfully, to acknowledge the rise and the fall of the abdomen and to acknowledge various feelings and thoughts. This is enough. Subsequently the instructor can give them more instruction after again examining the state of their perceptions and mental states (or making psycho-analysis). This procedure applies also to young people and chidren.

The practitioners should then prostrate themselves before their instructor in salutation and retire to their cells to begin the practice.

The instructor must go and see the students to examine their perceptions and mental states every day and give further instruction in practice according to the stage of knowledge or awareness achieved. For example when the practitioners have achieved the knowledge of discriminating mental and physical states (nāmarūpaparicchedañāna), the instructor should give further exercises, i.e. teach them to acknowledge their thoughts from then on whenever they want to crouch, to stretch or to rise.

When the practitioners have achieved the knowledge of discriminating cause and effect (paccayapariggahañana), acknowledgement of the movements while walking is increased two steps, to include, “Lifting, Treading”. In the sitting posture the practitioners should now acknowledge both the rising and falling of the belly and the posture. The important point is not to increase the number of exercises by more than two in the same day.

Question: What should the practitioners be taught?

Answer: They should perform various exercises as follows:

2. How to Practise Meditation#

2.1. Exercise 1#

While sitting, meditate on the abdomen which rises on inhaling and falls on exhaling. Acknowledge the rising and falling in your mind: “Rising, Falling,” according to whether it is a rise or a fall.

While reclining, do the same and acknowledge in a similar manner.

While standing, acknowledge the posture “Standing standing.”

While performing the mindful walking, acknowledge in stages as follows:

When the right foot advances, acknowledge the movement, “Right goes thus,” keeping the eyes fixed on the tip of the right foot; when the left foot advances, acknowledge the movement, “Left goes thus”, keeping the eyes fixed on the tip of the left foot. Acknowledge every step in this way. Having traversed the space allowed for the mindful walk and wishing to turn back, stand still first, acknowledge the posture, “standing, standing’” then turn back slowly and composedly, and acknowledge the movement “turning, turning.” Having turned right round, stand still first, acknowledging “standing, standing”, then continue to walk mindfully, acknowledging movements as before.

Practise each exercise until you are well experienced in it and can achieve good concentration, then pass on to the next one.

2.2. Exercise 2#

While sitting, acknowledge the awareness in three stages, viz:- “Rising : falling : sitting.”

While reclining, also acknowledge awareness in similar stages. (See Note below).

While standing, acknowledge your posture, “standing, standing”, until you walk or sit down.

While walking mindfully, perform Exercise 1 for about 10–30 minutes. Then change your acknowledgement of the movement, i.e. when you advance your right or left foot, acknowledge the movement in two stages, “Lifting, Treading”, for about 10–30 minutes.

Thus:

Acknowledge your movements while performing the mindful walk, “Right goes thus, left goes thus,” for about 10–30 minutes.

Acknowledge your movements while performing the mindful walk, “Lifting, Treading,” for about 10–30 minutes.

Note

(For this 2nd exercise concentrate, if only momentarily, on the postures until the images of sitting and reclining appear distinctly in your mind as if reflected in a mirror)

Note

Acknowledgement of “sitting” occurs after awareness of “falling” e.g. “Rising…… : falling…… : sitting.”

Sometimes, the abdomenal movements are not clearly recognized; when this happens it is useful to be mindful of “sitting” as soon as the awareness of “falling” has ceased or has become indistinct. The length of “falling” often varies; some examples may make the problem of acknowledgement clearer: e.g.

“Rising……… : falling……… : sitting……… : rising……… : falling……… : sitting………” and so on.

“Rising……… : rising…. : falling… falling… : sitting… : rising…”

“Rising………: rising……. : falling… falling… : falling… sitting… sitting… : rising…”

Explanation: Each word above (e.g. “rising”, “falling”) represents one’s acknowledgement; that is mentally saying the word. The dots(……) represent one’s awareness or mindfulness of the particular phenomenon. When awareness of one stage (such as rising) ceases (i.e. “Rising…”) acknowledgement and awareness of the next stage begins (e.g. “sitting…”).

2.3. Exercise 3#

While sitting, acknowledge awareness in four stages, “Rising : falling : sitting : touching.” Meditate upon the touching point as a circle about the size of tical coin ( a penny). Fix your mind -on that point while acknowledging.

While reclining, give acknowledgement in four stages, “Rising : falling : reclining : touching.”

While standing, acknowledge your posture, “standing, standing”.

While performing the mindful walking, do Exercise 1 and 2 first for about 10–20 minutes each; then change the acknowledgement, and while advancing your right or left foot, acknowledge the movement in three stages, viz, “Lifting, moving, treading.”

That is :

Acknowledge the movement of your feet, “Right goes thus, left goes thus,” for about 10–20 minutes.

Acknowledge “Lifting, treading,” for about 10–20 minutes.

Acknowledge “Lifting, moving, treading,” for about 10–20 minutes.

2.4. Exercise 4#

While sitting, acknowledge the rising and falling of the abdomen in four stages : “Rising, falling, sitting, touching”, as in Exercise 3, but now acknowledge, “Touching” several times (until the end of the out-going breath); i.e. “Rising, falling, touching, touching, etc.”

While reclining, acknowledge awareness in four stages, “Rising, falling, reclining, touching, touching, etc.“

While standing acknowledge your posture, “Standing standing.”

While performing the mindful walking, do as in Exercise 1,2, and 3 for about 10–20 minutes each, and then change the acknowledgement, i.e. while advancing with your right or left foot, acknowledge the movement in four stages, “Heel up : lifting : moving : treading,” for about 10–20 minutes

That is:

Acknowledge the movement of your feet, “Right goes thus, left goes thus” for about 10–20 minutes.

Acknowledge, “Lifting treading,” for about 10–20 minutes.

Acknowledge, “Lifting, moving, treading,” for about 10–20 minutes.

Acknowledge, “Heel up, lifting, moving, treading,” for about 10–20 minutes.

2.5. Exercise 5#

While sitting, be mindful of four stages, “Rising, falling, sitting, touching”. Find the point where the touch is most distinct, and concentrate on it when acknowledging : “touching.”

For Example :

“Rising, falling, sitting, touching” that is, touching with the right buttock. Concentrate on this position and acknowledge : “Touching.”

“Rising, falling, sitting, touching, ”that is, touching with the left buttock.

“Rising, falling, sitting, touching, ”that is, touching with the right knee. Concentrate on this position and acknowledge “Touching”

“Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” that is, touching with the left knee.

“Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” that is, touching with the right ankle.

“Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” that is, touching with the left ankle.

While reclining, acknowledge in four stages, viz. “Rising, falling, reclining, touching”.

While standing, acknowledge your posture, “Standing, standing,”

While performing the mindful walking, do as in Exercises 1,2,3 and 4 for about 10–20 minutes each, and then change the acknowledgement i.e. While advancing the right or left foot acknowledge the movements in five stages heel up, lifting, moving, dropping, treading“, for about 10–20 minutes.

To Summarize :

Acknowledge your movements in the mindful walking, “Right goes thus, left goes thus,” For about 10–20 minutes.

Acknowledge, “Lifting, Treading,” for about 10–20 minutes.

Acknowledge, “Lifting, moving, treading,” for about 10–20 minutes.

Acknowledge, “Heel up, lifting, moving, treading,” for about 10–20 minutes.

Acknowledge, “Heel up, lifting, moving, dropping treading,” for about 10–20 minutes.

2.6. Exercise 6#

While sitting be mindful as follows :

“Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” that is, touching with the right buttock.

“Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” that is, touching with the left buttock.

“Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” that is, touching with the right knee.

“Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” that is, touching with the left knee.

“Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” that is, touching with the right ankle,

“Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” that is, touching with the left ankle.

“Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” that is, touching at various points along the body.

While reclining, acknowledge thus : “Rising, falling, reclining, touching,” etc.

While standing, acknowledge your posture, “Standing, standing”.

While performing the mindful walking, acknowledge the movements :

“Right goes thus, left goes thus,” for about 5–10 minutes.

“Lifing, treading,” for about 5–10 minutes.

“Lifing, moving, treading,” for about 5–10 minutes.

“Heel up lifting, moving, treading,” for about 5–10 minutes.

“Heel up lifting, moving, dropping treading,” for about 5–10 minutes.

Now acknowledge a further stage : “Heel up : lifting : moving : dropping : touching : pressing.” for about 10–20 minutes.

2.7. Exercise 7#

Having performed the mindful walking to the extremity of the space allowed, stop to turn back, Before stopping, however, acknowledge your wish, “Wishing to stop,” and having stopped, acknowledge the action, “Stopped, stopped.” Before turning back. acknowledge your desire, “Wishing to turn, wishing to turn” and during turning round, acknowledge your action in steps “Turning, turning,”. Then stand still and acknowledge your posture, “Standing, standing”. Next perform the mindful walking again and acknowledge the movements as before.

When a desire arises to look right or left, acknowledge it thus: “Wishing to look aside, wishing to look aside”. Wishing to look aside, acknowledge the movement, “looking aside, looking aside.”.

Before bending or stretching, acknowledge your wish, “Wishing to bend,”. Or “Wishing to stretch,”. While actually doing the action, acknowledge it, “Bending, bending,” or “Stretching, streching,”.

Before grasping anything such as clothes, blankets, begging bowls, pots, jugs, and plates, acknowledge your wish, “Seeing, wishing to grasp.” While moving your hand, acknowledge the action, “Moving, moving,” While touching with your hand, acknowledge the action, “Touching.” While grasping it and moving it towards you, acknowledge the action, “Bringing, bringing”.

While you are eating or drinking or chewing or tasting or licking, acknowledge the action in similar manner.

For Example:

While perceiving the food, acknowledge the action. “Perceiving, Preceiving.”

While desiring to eat it, acknowledge the wish, “Desiring, Desiring.”

While advancing your hand towards it, ackowledge the action, “Moving, moving.”

While touching it, acknowledge the action “Touching, touching.”

While grasping or holding it, acknowledge the action, “Grasping” or “holding,”

While lifting it, acknowledge the action, “Lifting.”

While opening your mouth, acknowledge the action, “Opening.”

While the food is touching your mouth, acknowledge “Touching.”

While chewing, acknowledge the action, “Chewing.”

While swallowing, acknowledge the action, “Swallowing.”

While completing the eating, acknowledge the action, “Completing.”

While wishing to discharge excrement or urine, acknowledge your thought, “Wishing to excrete.” While excreting, acknowledge the action, “Excreting.”

When wishing to walk, stand, sit, sleep, get up, speak or keep silent, acknowledge the thoughts, “Wishing to walk,” “Wishing to stand,” “Wishing to sit,” “Wishing to sleep,” “Wishing to get up,” “Wishing to speak,” or “Wishing to keep silent.”

2.8. Exercise 8#

When seeing, acknowledge the perception, “Seeing, seeing.”

When hearing, acknowledge the perception, “Hearing, hearing.”

When smelling, acknowledge “Smelling, smelling.”

When tasting, acknowledge “Tasing, tasing.”

When touching, acknowledge “Touching, touching.”

When thinking, acknowledge either “Thinking, thinking,” or “Imagining, imagining.”

2.9. Exercise 9#

While acknowledging the rising and falling of the adbomen in the sitting posture, “Rising, Falling.” if any pain occurs, stop for a while, and acknowledge the pain, ache or stiffness, “Painful,” “aching” or “stiffness”. If the pain is too great to bear, stop the acknowledgement and go back to acknowledging the rising and falling of the abdomen If the pain is still there, change your posture.

If comfort arises, acknowledge it, “Comfort arising”

While reclining or standing, if any comfort or discomfort or indifference arises, acknowledge it, “Comfort arising” or “discomfort arising” or “indifference arising.”

If any pain arises during the mindful walk, stop first; then acknowledge the pain as described before, Note : If any mental image (Nimitta) such as light or a mountain arises, acknowledge it, “Seeing, seeing.” until it vanishes.

2.10. Exercise 10#

While sitting, if a need for something arises’ acknowledge it, “Needing, needing” or, “Desiring, desiring.”

If you wish to leave practice through, for example, boredom, or if you see or think of something and feel aversion, acknowledge your thought, e.g. “Discontented,” or “Hating.”

If you fell sleepy, acknowledge your feeling, “Sleepy”

If your mind is distracted, acknowledge your feeling, “Distracted.”

If you have any doubt, acknowledge your thought, “Doubting.”

If greed, anger, distraction and doubt, as examples of mental conditions, clear away, acknowledge that also.

While performing the mindful walking, if the mind is distracted stop walking and acknowledge your thought, “Distracted.” After the distraction has cleared away, go on with the mindful-walking.

2.11. Exercise 11#

If the mind is contented in sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, try to realize that it is a sensual contentment (Kāmagunā). Acknowledge your feeling, “Contented.”

When aversion arises, try to realize that it is hatred or a wish for revenge. Acknowledge it “Hating” or “Revenge.”

When the mind is jaded or apathetic, try to realize that this feeling is torpor and languor (Thinamidha). Acknowledge it, e.g. “Sleepy”.

If the mind is distracted, worried or depressed, try to realise that distraction and worry (Uddhaccakukkucca) have arisen, and acknowledge such feelings. “Distracted”, or Worrying“, or ”Depressed“.

When doubts in respect of mental and physical states (nāmarūpa), ultimate reality and the concepts (paññātti) arise, try to realise that this is sceptical doubt (Vicikicchā). Acknowledge it, “Doubting.”

2.12. Exercise 12#

Before sitting down, acknowledge your thought, “Wishing to sit down.” Then lower yourself slowly in stages and acknowledge the action, “Sitting down” until you touch the floor. Do the acknowledgement in 8–9–10 steps.

While acknowledging “Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” and an itch arises, acknowledge it, “Itching.” After the acknowledgement if the itch is still there and you want to scratch, acknowledge your desire “Wishing to scratch.” When your hand touches the spot, acknowledge the action, “Scratching.” When the itch disappears, acknowledge it, “disappearing,” and when you lower your hand from the spot, acknowledge your action, “Lowering,” until it is where it used to be. Then begin to concentrate on the rise and fall of the abdomen again and acknowledge your awareness, “Rising, falling, sitting, touching,”

2.13. Exercise 13#

Before beginning the meditation, make a wish as follows:

“May I be clearly aware of the coming-into-being and passing-away of all mental and physical phenomena appearing to the mind during twenty-four hours.”

Make this wish this whenever you wish, but spend at least twenty-four hours in meditation during this exercise.

Having made the wish as above, perform the mindful walking first; then sit down and acknowledge the rising and falling of the abdomen, “Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” as described before. Perform the two exercise in alternation throughout the twenty-four hours.

2.14. Exercise 14#

Perform the mindful walking first, then proceed as follows:

Make a wish that in a period of one hour, the phenomena of arising and ceasing shall appear at least five times.

If within this hour the phenomena of arising and ceasing appear distinctly, at least five times and possibly as many as sixty-five times reduce the period of the exercise to 30 minutes and make the wish that within these thirty minute the phenomena of arising and ceasing shall appear to you several times.

Make a wish in the same manner and reduce the period of the exercise down to 20–15–10–5 minutes. Within 5 minutes the phenomenon should appear at least twice, but it may appear as many as six times.

Alternate Walking and sitting exercises for twenty-four hours.

2.15. Exercise 15#

Perform the mindful walking first ; then in the sitting posture make a wish to attain steady concentration for 5 minutes. Next acknowledge “Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” etc. The resolution is fulfilled if the mind abides in concentration and becomes unconscious of outside phenomena for a 5 full minutes. Keep a careful check on the time and if this exercise cannot be continued for 5 minutes, repeat it until you are successful. Then try to increase the period of full concentration.

Make a resolve to obtain steady concentration without consciousness of outside phenomena for 10 muinutes. If this cannot be achieved yet, try again until you are quite experienced. Then practise further for 15–20–30 minutes to 1 hour, one and a half hour, 2–3–4–5–6–7–8 hours, up to 24 hours.

The number of minutes and hours is to be reckoned from the point of steady concentration with nonconsciousness onwards. In such a condition, we do not experience any feeling. The period wished for being fulfilled, consciousness will return of its own accord as in waking, but this is not waking.

2.16. Exercise 16#

Practitioners who have become experienced in practice and would like to qualify as future instructors should perform a Special exercise as follows:

First exercise, to be done in one day.

Perform the mindful walking first, then sit as usual and resolve that within one hour the mental and physical states in the process of arising and ceasing shall appear distinctly. Acknowledge ilie awareness, “Rising, falling, sitting, touching”, etc. to complete one full hour. While acknowledging, you will perceive the arising ,md ceasing of the mental and physical states more distinctly than before. This insight knowledge is called Udyabbayañāṇa.

After this, resolve that within the succeeding hour only mental and physical states in cessation (or in their passing-away) shall be perceived. Then acknowledge the awareness, “Rising, lulling, sitting, touching,” etc. to complete one full hour. While acknowledging, only the passing-away of the mental and physical states will appear, that is, the cessation appears more distinctly than before. This insight is called Bhaṃganñāṇa.

Second exercise, to be done in one day.

Perform the mindful walking first, then sit as usual and resolve that within one hour the Bhayañāna shall arise in you. Acknowledge the perceptions, “Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” etc. to complete one full hour. While thus acknowledging, fear will arise in your mind. This insight knowledge is therefore known as Bhayañāṇa.

In the succeeding hours, resolve that the Adinavanana shall arise, and acknowledge the perceptions, “Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” etc. to complete one full hour. While acknowledging in the sitting posture, there will arise all kinds of afflictions latent in the mental and physical states, such as pain, aching, impermanence, suffering, and anattā. This knowledge is known Adinavañāṇa.

In the third successive hour resolve that the Nibbid āñāna shall arise. Acknowledge the awareness, “Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” to complete one full full hour. While acknowledging in the sitting posture there will arise revulsion, the mental and physical states appear to you as ugly refuse, full of afflictions and suffering, unpleasant and disgusting, This knowledge is called Nibbidāñāṇa.

Third exercise, to be done in one day.

Perform the mindful walking first ; then sit as usual and resolve that within this hour the Muñcitukamyatāñana shall arise. Acknowledge the perceptions “Rising, falling, sitting, touching”, to complete one full hour. While acknowledging in the sitting posture, there will arise a wish to retire, to escape into seclusion. This knowledge is known as Muñcitukamyatāñāṇa.

In the succeeding hour resolve that within this hour the Patisamkhañāna shall arise and acknowledge the perceptions, “Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” etc. to complete one full hour. While acknowledging in the sitting posture, there will arise an effort to use one’s energy to seek detachment and to escape into seclusion. This knowledge is Patisamkhanñāṇa.

In the third successive hour resolve that within this hour the Sarnkharūpekkhañāna, shall arise and acknowledge the perceptions. “Rising, falling, sitting, touching,” etc., to complete one full hour. While acknowledging in this posture there will arise equanimity with regard to mental and physical states. This knowledge is know as Sarnkharūpekkhañāṇa.

Q: What are the benefits of performing Insight Meditation (Vipassanā) in the way described? Please expound a little further.

A: There are several benefits as follows :

To give certainty of Truth, and not to be deceived by and not to hold fast to concepts (paññāat ti) which are mere mundane conventions.

To make people truly cultured, having good morals.

To make people love one another, make them feel their unity and to be compassionate towards each other, and to make them have gladness and appreciation when they see others who are joyful.

To bring about a better standard of human behaviour.

To make people know themselves and how to govern themselves.

To cultivate humility.

To bring about realisation of human unity.

To make people abide in gratitude.

To make people Bhikkhus of the Ariya Sangha, as this practice of Dhamma is for the following attainments :-

To be without the five hindrances (Nivarana)

To be without the five stands of sensual pleasure (Kamaguna)

To be without the factors of the “fivefold clinging to existence” (Upādānakakhandha)

To be without the five lower fetters ; the Ego-illusion (Sakkayaditthi), sceptical doubt (Vicikicchā), attachment (or clinging) to mere rules and ritual (Silabbataparamasa), sensuous desire (Kamachanda) and ill-will (Vyāpada)

To be free from the 5-fold destinies (gati).

To be without selfishness in any form ; selfishness in lodgings, selfishness in family, selfishness in property, selfishness in rank and selfishness in Dhamma.

To be without the five higher fetters, set out as craving for life in the world of pure form (Rūparāga), craving for the formless world (Arūparāga), pride, distraction and ignorance.

To be without Cetokhila, the five “nails” which limit the mind, comprising doubt in the Buddha the Dhamma and the Sangha, and in the training and anger against one’s fellow-monks.

To be without Cetovinibandha, the five fetters which hinder the mind from making right exertion ; namely : lust for sensuous objects, for the body, for visible things, for eating and sleeping, and leading the monk’s life for the sake of heavenly rebirth.

To be free from sorrow, grief, woe and lamentation and attain the Path, Fruition and Nibbāna.

The highest blessing is to succeed as an adept or Arahant. Of lower qualifications are the Never Returner (Anagami), the Once Returner (Sakadagami), and the Stream Winner (Sotapana). Still lower down on the scale are the commoners who have a steady determination to go along the path of righteousness according to the principle:

“Iminā pana ñāñanena samannāgato vipassako Buddhasāsane laddhassāsa laddhapatittho niyagatiko jūlasotapanno nama hoti,” meaning, “When the practitioners who are endowed with wisdom have practised Insight Meditation (Vipassanā), they will succeed as minor Sotāpanas, become light hearted, obtain true refuge in Dhamma and have a steady determination to go along the path of righteousness.”

Also, the practitioners who have practised Insight Medetation (Vipassana) and gained insight into the arising and ceasing of mental and physical states, are to be considered as blessed as stated thus :

“Yoca vassasatam jive apassam udyabbayam akāham jivitam seyyo passto udyabbayam” “Those who perceive the arising and ceasing of mental and physical states, even though they live for a day only, are far better than those who never see the arising and ceasing of mental and physical states and live a hundred years.“

Q: How long would it take to succeed in the practice of Insight meditation?

A: If the practice is done continuously for 1 day 15 days 1 month, 2–3–4–5–6–7 months or 1–2–3–4–5–6–7 years one would succeed according to whether one’s previous merits are strong or weak. The time specified is for the practitioners of medium previous merits. Those with great previous merits, when they practise in the morning, can succeed in the evening, and when they practise in the evening, can succeed in the morning according to the words of the commentator:

“Tikkhapaññam pana sandhāya pātova anusittho sayaṃ visesam adhigāissati sāyam anusittho pato visesam adhigmissatiti vuttam”

“Thus was it said ; to be instructed in the morning and to attain the divine Dhamma in the evening, to be instructed in the evening and to attain the divine Dhamma in the morning, is the way of Tikkha persons endowed with great previous merits”.

Explanation of the practice of insight meditation (vipassana) ends here.

2.17. Translator’s note#

This booklet was originally produced by the Central office of the Division of Vipassana Dhura at Mahadhat Monastery several years ago. When the printing committee of Wat Mahadhat decided to reprint it I was asked to check the English. It became obvious that simple correction would not be sufficient, and rewriting was in order. I have frequently referred to the original Thai text, which is remarkably clear and well-organized, in order to clarify several sections of the text and fill in parts which were missing. Obviously some of the experiences described in this book defy expression in any language, but I have aimed for clarity whenever possible.

This part of the book is not intended for people with little experience of meditation. It is intended for meditation teachers and experienced non-Thai meditators who may find it difficult to get a good translation by a competent interpreter.

3. Manual for checking your vipassana kamatthana progress#

3.1. Nāmarupa pariccheda Ñana#

In this Ñana or state of wisdom or knowledge, the meditator is able to distinguish NAMA from RUPA For example, he is aware that the rising and falling movements of the abdomen are RUPA and the mind which acknowledges these movements is NAMA. A movement of the foot is RUPA and the consciousness of that movement is NAMA.

The meditator can distinguish between NAMA and RUPA with regard to the five senses as follows :-

When seeing a form, the eyes and the colour are RUPA and the consciousness of the seeing is NAMA.

When hearing a sound, the sound itself and the hearing are RUPA and consciousness of the hearing is NAMA.

When smelling something, the smell itself and the nose are RUPA, and the consciousness of the smell is NAMA.

When tasting something, the taste and the tongue are RUPA, and the consciousness of taste is NAMA.

When touching something, whatever is cold, hot, soft or hard to the touch is RUPA and consciousness of the contact is NAMA.

In conclusion, in this Ñana the meditator realizes that the whole body is RUPA and the mind (or consciousness of the sensations of the body) is NAMA. only NAMA and RUPA exist. There is no being, no individual self, no T, no ‘he’ or ‘she’ etc. When sitting, the body and its movement are RUPA and awareness of the sitting is NAMA. The act of standing is RUPA and awareness of the standing is NAMA. The act of walking is RUPA and the awareness of the walking is NAMA.

3.2. Paccaya pariggaha Ñana#

(Knowledge of discerning the condition of mentality/materiality)

In some instances RUPA is the cause and NAMA is the effect, for example when the abdomen rises and consciousness follows. At other times NAMA is the cause and RUPA is the effect, for example the wish to sit is the cause and the sitting is’ the effect ; in other words volitional activity precedes physical action.

Some symptoms of this ÑANA

The abdomen may rise but fail to fall.

The abdomen may fall deeply and remain in that position.

The rising and falling of the abdomen seems to have disappeared but when touched by the hand movements can still be felt.

At times there are feelings of distress of varing intensity.

Some meditators may be much disturbed by visions or hallucinations.

The rising and falling of the abdomen and the acknowledgement of the movements function at the same time.

One may be startled sometimes bending forwards or backwards.

The meditator conceives that this existance, the next and all existances only derive from the interaction of cause and effect. They consist of NAMA and RUPA only.

A single rise of the abdomen has two stages.

3.3. Sammasana Ñana#

(Knowledge of comprehending mentality/materiality as unsatisfactory and not-self)

Some characteristics of this ÑANA :-

One considers NAMA and RUPA through the five senses. One is aware of the three characteristics, ANICCA (impermance) DUKKHA (suffering) and ANATTA (non-self) which are referred to collectively as TRILAKKHANA.

One rising movement of the abdomen has three sections, called UPADHA, DTITI and BHANKA or coming into existance, continuity and vanishing. One falling movement of the abdomen has three sections.

There are feelings of distress which disappear only slowly; after seven or eight acknowledgements.

There are many NIMITTAS (mental images) which disappear slowly after several acknowledgements).

The rising and falling movements of the abdomen may disappear for either a long or short interval.

Breathing may be fast, slow or obstructed.

The mind may be distracted which shows that it is aware of the TRILAKKHANA or the three characteristics.

The meditator’s hands or feet may clench or twitch.

Some of the ten VIPASSANUPAKILESAS (defilements of insight) may appear in this ÑANA.

3.3.1. The Ten Vipassanupakilesas#

3.3.1.1. OBHASA (Illumination)#

The meditator may be aware of the following manifestations of light :-

He may be aware of light similar to that of firefly, a torch or a car headlamp.

The whole room may be lit up sufficiently to enable the meditator to see his body.

He may be aware of light which seems to pass through the wall.

There may be a light which enables him to see various places in front of him.

There may be a bright light as though a door has come open. Some meditators lift up their hands as if to shut it, others open their eyes to see what caused the light.

A vision of brightly coloured flowers surrounded by light may be seen.

Miles and miles of sea may be seen.

Rays of light seem to be emitted from the meditators heart and body.

Hallucinations, such as seeing an elephant, may occur.

3.3.1.2. PĪTI (Joy or rapture)#

There are five kinds of PITI : KHUDDAKA (minor rapture) ; KHANIKA (momentary joy) ; OKKANTIKA (flood of joy) ; UBBENKA (uplifting joy) ; and PHARANA (pervading rapture).

KHUDDAKA PĪTI (Minor rapture)

This state is characterized by the following :-

The meditator may be aware of white colour.

There may be a feeling of coolness or dizziness and the hairs of the body may stand on end.

Tears may fall and there may be feelings of terror.

KHANIKĀ PĪTI (Momentary joy)

Characteristics of this Piti include :-

Flashes of light light may be seen.

Sparks of light may be seen.

Nervous twitching may occur.

There may be a feeling of stiffness all over the body.

There may be a feeling as if ants are climbing over the body.

The meditator may feel hot all over his body.

The meditator may shiver.

Various red colours may be seen.

Body hair may rise slightly.

The meditator may feel itchy as if ants are scrambling on his face and body.

OKKANTIKA PĪTI (Flood of joy)

Characteristics of this Piti include :-

The body may shake and tremble.

The face, hands and feet may twitch

There may be violent shaking as if the bed is going to turn upside down.

Nausea and at times actual vomiting occurs.

There may be a rhythmic feeling like waves breaking on the shore.

Ripples of energy may seem to flow over the body.

The body may vibrate like a stick which is fixed in a flowing stream.

A light yellow colour may be observed.

The body may bend to and fro.

UBBENKA PĪTI (Uplifting joy)

Characteristics of this Piti include :-

The body feels as if it is extending or moving upwards.

There may be a feeling as though lice are climbing on the face and body.

Diarrhea may occur.

The body may bend forwards or backwards.

One may feel that one’s head has been moved backwards and forwards by somebody.

There may be a chewing movement with the mouth either open or closed.

The body sways like a tree being blown by the wind,

The body bends forwards and may fall down.

There may be fidgeting movements of the body,

There may be jumping movements of the body,

Arms and legs may be raised or may twitch.

The body may be bent forwards or may recline,

A silvery grey colour may be observed.

PHARANA PĪTI (Pervading rapture)

Characteristics of this Piti include :-

A feeling of coldness spreads through the body.

Peace of mind sets in occasionally.

There may be itchy feelings all over the body.

There may be drowsy feelings and the meditator may not wish to open his eyes.

The meditator has no wish to move.

There may be a flushing sensation from feet to head or vice versa.

The body may feel cool as if taking a bath or touching ice.

The meditator may see blue or emerald green colours,

An itchy feeling as though lice are crawling on the face may occur.

This is the end of the description of the five Pitis.

3.3.1.3. PASSADHI#

The third defilement of Vipassana is PASSADHI which means tranquility or mental factors and consciousness. It is characterized as follows :-

There may be a quiet, peaceful state resembling the attainment of insight,

There will be no restlessness or mental rambling.

Mindful acknowledgement is easy.

The meditator feels comfortably cool and does not fidget.

The meditator feels satisfied with his powers of acknowledgement.

There may be a feeling similar to falling asleep.

There may be a feeling of lightness.

Concentration is good and there is no forgetfulness.

Thoughts are quite clear.

A cruel, harsh or merciless person will realize that the Dhamma is profound. As a result he will give up doing bad and will perform only good actions instead.

A criminal or a drunkard will be able to give up bad habits and will change into quite a different man.

3.3.1.4. SUKHA#

The fourth defilement of Vipassana is SUKHA which means bliss and has the following characteristics :-

There may be a feeling of comfort.

Due to pleasant feelings the meditator may not wish to stop but continue practising for a long time.

The meditator may wish to tell other people of the results which he has already gained,

The meditator may feel immeasurably proud and happy.

Some say that they have never known such happiness.

Some feel deeply grateful to their teachers.

Some meditators feel that their teacher is at hand to give help.

3.3.1.5. SADDHĀ#

The next defilement of Vipassana is SADDHA which is defined as fervour, resolution or determination and has the following SADDHA characteristics :-

The practitioner may have too much faith.

He may wish everybody to practice Vipassana.

He may wish to persuade those he comes in contact with to practice.

He may wish to repay the meditation centre for its benefaction.

The meditator may wish to accelerate and deepen his practice.

He may wish to perform meritorious deeds, give alms and build and repair Buddhist buildings and artifacts.

He may feel grateful to the person who persuaded him to practice.

He may wish to give offerings to his teacher.

A meditator may wish to be ordained as a Buddhist monk,

He may not wish to stop practicing.

He might wish to go and stay in a quiet, peaceful place.

The meditator may decide to practice whole-heartedly.

3.3.1.6. PAGGAHA#

The next defilement of Vipassana is PAGGAHA which means exertion or strenuousness and is defined as follows :-

Sometimes the meditator may practice too strenuously.

He may intend to practice rigorously, even unto death.

The meditator over exerts himself so that attentiveness and clear-consciousness are weak causing distraction and lack of Samadhi (concentration)

3.3.1.7. UPATTHANA#

which means mindfulness, is the next defilement of Vipassana to be considered and it is characterized by the following :-

Sometimes excessive concentration upon thought causes the meditator to leave acknowledgement of the present and inclines him to think of the past and the future,

The meditator may be unduly concerned with happenings which took place in the past.

The meditator may have vague recollections of past lives.

3.3.1.8. ÑANA#

The next (Vipassanupakilesa) to be considered is NANA which means knowledge and is defined as follows :-

Theoretical knowledge may become confused with practice. The meditator misunderstands but thinks that he is right. He may become fond of ostentatiousness and like contending with his teacher.

A meditator may make comments about various objects. For example when the abdomen rises he may say ‘arising’ and when it falls he may say ‘ceasing’.

The meditator may consider various principles which he knows or has studied.

The present cannot be grasped. Usually it is ‘thinking’ which fills up the mind. This may be referred to as ‘thought-based knowledge.’ Jinta Ñana.

3.3.1.9. UPEKKHÂ#

The ninth defilement of Vipassana is UPEKKHA which has the meaning of not caring or indifference…. It can be defined as follows :-

The mind of the meditator is indifferent, neither pleased or, displeased, nor forgetful. The rising and falling of the abdomen is indistinct and at times imperceptible.

The meditator is unmindful, at times thinking of nothing in particular.

The rising and falling of the abdomen may be intermittently perceptible.

The mind is undisturbed and peaceful.

The meditator is indifferent to bodily needs.

The meditator is unaffected when in contact with either good or bad objects. Mindful acknowledgement is disregarded and attention is allowed to follow exterior objects to a great extent.

3.3.1.10. NIKANTI#

The tenth Vipassanupakilesa is NIKANTI which means ‘gratification’ and it has the following characteristics :-

The meditator finds satisfaction in various objects.

He is satisfied with light, joy, happiness, faith, exertion, knowledge and even-mindedness.

He is satisfied with various Nimittas (mental images).

That is the end of the section dealing with the ten Vipassanupakilesas.

3.4. Udayabbaya Ñana#

The fourth ÑANA to be considered is UDAYABBAYA ÑANA which may be translated as knowledge of contemplation on the rise and fall. In this ÑANA the following may occur :-

The meditator sees that the rising and falling of the abdomen consists of 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6 stages.

The rising and falling of the abdomen may disappear intermittently.

Various feelings disappear after two or three acknowledgements.

Acknowledgement is clear and easy.

Nimittas disappear quickly, for instance after a few acknowledgements of ‘seeing, seeing’.

The meditator may see a clear, bright light.

The beginning and the end of the rising and falling movements of the abdomen are clearly perceived.

While sitting, the body may bend either forwards or backwards as though falling asleep. The extent of the movement depends on the level of concentration. The breaking of ‘Santati’ or continuity can be observed by the expression of the following characteristics :

If the rising and falling movements of the abdomen become quick and then cease, Anicca (impermanence) appears clearly but Anatta (non-self) and Dukka (suffering) still continue.

If the rising and falling movements become light and even and then cease, Anatta (non-self) appears clearly. However Anicca and Dukka still continue.

If the rising and falling of the abdomen becomes stiff and impeded and then ceases, Dukka (suffering) is clearly revealed, but Anicca and Anatta continue.

If the meditator has good concentration, Samadhi, he may experience a ceasing of breath at frequent intervals. He may feel as if he is falling into an abyss or going through an air pocket on a plane, but in fact the body remains motionless.

3.5. Bhanga Ñana#

BHANGA ÑANA is the fifth knowledge or state of wisdom to be considered here. It means ‘Knowledge of contemplation on dissolution’ and it has the following characteristics :-

The ending of the rising and falling movements of the abdomen are clear.

The objects of the meditator’s concentration may not be clear. The rising and falling movements of his obdomen may be vaguely perceived.

The rising and falling movements may disappear. It is however noticed by the practitioner that RUPA disappears first followed by NAMA. In fact the disappearance takes place almost simultaneously because of the swift functioning of the Citta (mind).

The rising and falling movements are distinct and faint.

There is a feeling of tightness enabling one to see the continuity of the rising and falling. The first state of consciousness ceases and a second begins enabling the meditator to know the ceasing.

Acknowledgement is insufficiently clear because its various objects appear to be far away.

At times there is only the rising and falling, the feeling of self disappears.

There may be a feeling of warmth all over the body,

The meditator may feel as though he is covered by a net.

Citta (mind or consciousness) and its object may disappear altogether.

At first RUPA (material or physical) ceases, But Citta remains, however consciousness soon disappears as well as the object of consciousness.

Some meditators feel that the rising and falling of the abdomen ceases for only a short time, while others feel that the movement stops for 2–4 days until they get bored. Walking is the best remedy for this.

Upada, Thiti and Bhanga, that is the coming into being, continuity and passing away stages of both NAMA and RUPA are present but the meditator is not interested, observing only the stage of passing,

The internal objects of meditation, that is the rising falling movements of the abdomen are not clear. External objects, trees etc. seem to shake,

Everything gives the impression of looking at a field of fog, vague and obscure,

If the meditator looks at the sky it seems as it there is vibration in the air.

Rising and falling suddenly ceases and suddenly reappears.

3.6. Bhaya Ñana#

The sixth state of knowledge is BHAYA ÑANA or ‘Knowledge of the appearance as terror’. The following characteristics can be observed :-

At first the meditator acknowledges objects but the acknowledgements vanish together with the consciousness.

A feeling of fear occurs but it is unlike that generated by seeing a ghost.

The disappearance of NAMA and RUPA and the consequent becoming nothing induces fear.

The meditator may feel neuralgic pain similar to that caused by a nervous disease when he is walking or standing.

Some practitioners cry when they think of their friends and relatives.

Some practioners are very much afraid of what they see, even if it is only a water jug or a bed post.

The meditator now realizes that NAMA and RUPA which were previously considered to be good, are completely insubstantial.

There is no feeling of happiness, pleasure or enjoyment.

Some practioners are aware of the feeling of fear but are not controlled by it.

3.8. Nibbida Ñana#

NIBBIDA ÑANA or ‘Knowledge of contemplation on dispassion,’ is the eighth NANA. It has the following characteristics :-

The meditator views all objects as tiresome and ugly.

The meditator feels something akin to laziness but the ability to acknowledge objects clearly is still present.

The feeling of joy is absent and the meditator feels bored and sad as though he has been separated from what he loves.

The practitioner may not have experienced boredom before but now he really knows what boredom is.

Although previously the meditator may have thought that only hell was bad, at this stage he feels that only Nibbana, not a heavenly state, is really good. He feels that nothing can compare with Nibbana so he deepens his resolve to search for it.

The meditator may acknowledge that there is nothing pleasant about NĀMA and RUPA.

The meditator may feel that everything is bad in every way and there is nothing that can be enjoyed,

The meditator may not wish to speak to or meet anybody. He may prefer to stay in his room.

The meditator may feel hot and dry as though being scorched by the heat of the sun.

The meditator may feel lonely, sad and apathetic, k. Some lose their attachment to formerly desired fame and fortune. They become bored realizing that all things are subject to decay. All races and beings, even the Devas and Brahmas are likewise subject to decay. They see that where there is birth; old age, sickness and death prevail. So there is no feeling of attachment. Boredom therefore sets in together with a strong inclination to search for Nibbana.

3.9. Muncitukamayatā Ñana#

The ninth Ñana to be considered is MUCITUKAMAYATA NANA which can be translated as ‘The knowledge of the desire for deliverance.’ This Ñana has the following characteristics :-

The meditator itches all over his body. He feels as if he has been bitten by ants or small insects, or he feels as though they are climbing on his face and body.

The meditator becomes impatient and cannot make acknowledgements while standing, sitting, lying down or walking.

He cannot acknowledge other minor actions.

He feels uneasy, restless and bored.

He wishes to get away and give up meditation.

Some meditators think of returning home, because they feel that their Parami (accumulated past merit) has been insufficient. As a result they start preparing their belongings to go home. In the early days this was termed ‘The Ñana of rolling the mat.’

3.10. Patisankhā Ñana#

The tenth ÑANA to be considered here is PATISANKHA ÑANA or the ‘Knowledge of reflective contemplation.’ The following characteristics may be observed :-

The meditator may experience feelings similar to being pierced by splinters throughout his body.

There may be many other disturbing sensations but they disappear after two or three acknowledgements.

The meditator may feel drowsy.

The body may become stiff as if the meditator is entering Phalasamapati (a Vipassana trance) but Citta (mind or consciousness) is still active and the auditory channel is still functioning.

The meditator feels as heavy as stone.

There may be a feeling of heat throughout the body.

He may feel uncomfortable.

3.11. Sankhārupekhā Ñana#

‘Knowledge of equanimity regarding all formations’ or SANKHARUPEKHA ÑANA follows. This Ñana has the following characteristics :-

The meditator does not feel frightened or glad, only indifferent. The rising and falling of the abdomen is clearly acknowledged as merely being NAMA and RUPA.

The meditator feels neither happiness nor sadness. His presence of mind and consciousness are clear. NAMA and RUPA are clearly acknowledged.

The meditator can remember and acknowledge without difficulty.

The meditator has good concentration. His mind remains peaceful and smooth for a long time, like a car running on a well paved road. The meditator may feel satisfied and forget the time.

Samadhi (concentration) becomes firm, somewhat like pastry being kneaded by a skilled baker.

Various pains and diseases such as paralysis or nervousness may be cured.

It can be said that the characteristics of this ÑANA are ease and satisfaction. The meditator may forget the time which has been spent during practice. The length of time spent sitting might even be as much as one hour instead of the half hour which was originally intended.

3.12. Anuloma Ñana#

ANULOMA ÑANA or ‘Conformity knowledge’, ‘Adaptation knowledge’ follows. This Ñana can be divided into the following stages :-

Wisdom derived from the preliminary Ñanas starting with the fourth.

Wisdom derived from the higher Ñanas ie. The 37 Bodhipakkiyadharma , qualities contributing to or constituting enlightenment; the 4 Iddhipada or paths of accomplishment; the 4 Sammappadhara, right or perfect efforts; the 4 Satipatthana or foundations of mindfulness; the 5 Indriya or controlling faculties and the five Bhala or powers etc.

Anuloma Ñana has the characteristics of Anicca, Dukkha and Anatta.

Anicca (impermanance) He who has practised charity and kept the precepts will attain the pa’h by Anicca. The rising and falling of the abdomen will become quick but suddenly cease. The meditator is aware of cessation of movement as the abdomen rises and falls or the cessation of sensation when sitting or touching. Quick breathing is a symptom of Anicca, The knowledge of this ceasing whenever it occurs is called Anuloma Ñana. However this should actually be experienced by the meditator, not just imagined.

Dukkha (suffering) He who has practised Samatha (concentration) will attain the path by way of Dukkha. Thus when he acknowledges the rising and falling of the abdomen or sitting and touching, he feels stifled. When he continues to acknowledge the rising and falling of the abdomen or the sitting and touching, a cessation of sensation will take place. A characteristic of path attainment by way of Dukkha is unbearability. The knowledge of the ceasing of the rising and falling of the abdomen, or the cessation of sensation when sitting or touching is Anuloma Nana.

Anatta (No-self) He who has practised Vipassana or was interested in Vipassana in former lives will attain the path by Anatta. Thus the rising and falling of the abdomen becomes steady, evenly-spaced and then ceases. The rising and falling movements of the abdomen or the sitting and touching will be seen clearly. Path attainment by Anatta is characterised by a smooth, light movement of the abdomen.

When the movements of the abdomen continue evenly and lightly, that is Anatta. Anatta means ‘without substance’ ‘meaninglessness’ and ‘uncontrollability’.

The ability to know clearly the cessation of the rising and falling movements of the abdomen, or the cessation of sensation when sitting and touching is called Anuloma Ñana.

3.12.1. The Four Noble Truths#

In the Anuloma Ñana, the four noble truths appear clearly and distinctly as follows :-

SAMUDAYA SACCA. This truth is perceived when the abdomen begins to rise or begins to fall, and it occurs at the point that the meditator is about to enter the next Nana, which is called the Gotrabhu Ñana. Samudaya Sacea is also referred to as Rupa Jati and Nama Jati. It is the point of origination of Nama and Rupa. It is the point of origination of both the beginning of the rising and the beginning of the falling movements of the abdomen. Nama Jati is the beginning of Nama and Rupa Jati is the beginning of Rupa. Real perception and experience of these truths is called ‘Samudaya Sacca’.